Christianophobia and anti-Christian hatred in Europe

Christianophobia & anti-Christian hatred in Europe

In 2023, 2,444 hate incidents targeting Christians were recorded in Europe, including 232 physical assaults.[1] These numbers, which have steadily increased in recent years, reflect a troubling rise in anti-Christian intolerance. Attacks, church desecrations, bans on prayer, and dismissals for religious reasons are becoming more common, often without eliciting any institutional response. This leads to the marginalization of Christians in public life, as well as the gradual criminalization of convictions inspired by Christianity. Shedding light on this phenomenon, referred to as Christianophobia, anti-Christianism, anti-Christian hatred, or anti-Christian crimes, is necessary to help the public and policymakers better protect religious freedom in Europe.

1. Definition and Recognition of Christianophobia

1.1 What is Christianophobia?

Christianophobia refers to hatred, discrimination, or violence directed at people, places, or symbols because of their Christian identity. It includes insults, vandalism, threats, discrimination, or assaults motivated by the victim's Christian faith, as well as violations of religious freedom.

According to the international definition of “intolerance and discrimination based on religion or belief,”[2] Christianophobia includes any distinction, exclusion, restriction, or preference based on the Christian religion that has the purpose or effect of hindering the enjoyment of fundamental rights on the basis of equality.

Christianophobia affects all Christian denominations: Catholic, Protestant, Orthodox, and is developing in a climate of growing hostility toward Christianity and its values. It poses a threat to social cohesion and religious freedom.

One of the most serious acts of Christianophobia was the January 25, 2023, attack in Algeciras, Spain: a man armed with a machete attacked two churches, killing a sacristan and injuring a priest while shouting “death to Christians.” This act, labeled as terrorism by authorities, represents the most violent form of Christianophobia. Other, more frequent manifestations, such as church arson, desecration of religious statues, or hateful graffiti on places of worship, are reported weekly in several European countries.

1.2 Debates on the Term “Christianophobia”

Several terms are used to describe hostility toward Christianity, its values, and its followers. Among them, the word “Christianophobia” is increasingly present in public discourse and has started to be adopted by certain institutions, including the United Nations. However, the term remains controversial. Derived from the Greek suffix “-phobia,” it implies an irrational fear. Yet anti-Christian hatred does not necessarily stem from fear but may result from ideological hostility, cultural rejection, or political or historical conflicts. For this reason, some prefer alternative expressions such as “anti-Christianism,” “hatred against Christians,” or “anti-Christian intolerance,” which are considered more precise.

The term “Christianophobia” has largely gained traction as a counterpart to the term “Islamophobia,” which was popularized by political actors such as the Organization of Islamic Cooperation. That neologism, initially intended to highlight hate crimes against Muslims, has at times become a tool of censorship in certain states (Pakistan, Turkey) or groups (Muslim Brotherhood) seeking to ban any criticism of Islam. However, it is not desirable to sacralize religions or to use such terms to introduce restrictions on free speech akin to blasphemy laws. We do not aim to ban critique or debate surrounding Christianity, which must remain possible in a free society. Rather, the goal is to name and combat the hatred, violence, and discrimination suffered by believers solely because of their faith.

Despite its limitations, the use of the word “Christianophobia” remains strategic. It helps designate a reality still too often ignored: the growing hostility toward Christians in secularized Christian societies. This rejection manifests not only in public and institutional spaces but also in social, professional, and even family relationships. It is not a marginal phenomenon: according to the OSCE, acts motivated by the victim’s Christian faith fall under the category of hate crimes.[3] Thus, like the term “Islamophobia,” whose ideological uses we also critique, the word “Christianophobia” still serves as a useful tool for amplifying the voices of discriminated Christians and prompting institutional action. Its use, though imperfect, is currently legitimate.[4]

1.3 Christianophobia in International and European Law

Christianophobia is recognized, either explicitly or implicitly, by several international organizations responsible for protecting fundamental rights. These institutions sometimes use different wording, such as “discrimination based on religion,” but some do explicitly identify hatred directed at Christians.

- The United Nations (UN) explicitly mentions Christianophobia in several official resolutions. Resolution 72/177, for example, calls on states to prevent acts motivated by Christianophobia, alongside antisemitism and Islamophobia. Resolution 77/318, adopted by the General Assembly in 2023, expresses concern over increasing cases of discrimination, intolerance, and violence targeting members of numerous religious communities, including Christians.

- The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) uses an operational definition of hate crimes. According to the OSCE, an act is considered an anti-Christian hate crime when it combines a criminal offense with a motivation targeting a person or property based on their real or perceived Christian identity. The OSCE documents these incidents annually through its Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR). On July 28, 2025, the OSCE published a practical guide: "Understanding Anti-Christian Hate Crimes and Addressing the Security Needs of Christian Communities."[5]

- The European Union (EU) does not recognize Christianophobia as a distinct category of hate speech or hate crime. Hostile acts toward Christians fall under the broader category of religion-based hate, without specific designation. However, in written questions to the Commission and in the media, several Members of the European Parliament have called for the creation of a dedicated coordinator position to combat anti-Christian hatred, similar to the existing roles for antisemitism and anti-Muslim hatred.

- The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR)prohibits all discrimination based on religion (Article 14 of the Convention) but does not use the term “Christianophobia” in its case law. This lack of explicit recognition raises questions about equal treatment of religious groups, especially since it has recognized “antisemitism” (Pavel Ivanov v. Russia, 2007; Dieudonné M’Bala M’Bala v. France, 2015) and “Islamophobia” (Leroy v. France, 2008; Paksas v. Lithuania [GC], 2011; A.S. v. France [GC], 2014) in its case law and official documents (Guide on Article 17, “Prohibition of abuse of rights”).

- The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE)has already used the term “Christianophobia.” In its Recommendation 1957 on “Violence against Christians in the Middle East” (2011), it invited member states “to produce, promote and disseminate educational materials addressing anti-Christian stereotypes and prejudices, as well as Christianophobia in general.”

2. Key Figures and Typology of Anti-Christian Acts in Europe

2.1 Hate Crimes Against Christians, 2023 Statistics and Trends in Europe

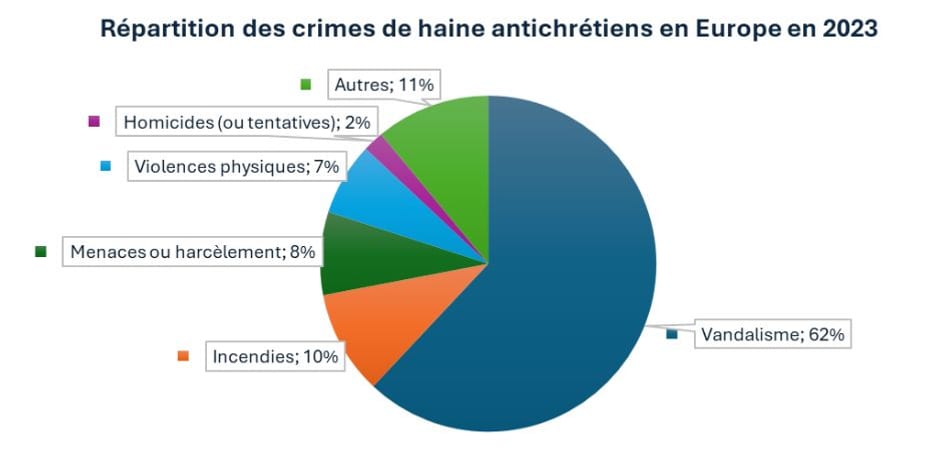

In 2023, the Observatory on Intolerance and Discrimination Against Christians in Europe (OIDAC) recorded 2,444 anti-Christian hate crimes across 35 European countries. This number, higher than in 2022, reflects an intensification of violence targeting churches, religious symbols, and individuals because of their Christian faith. Among these incidents, 232 assaults were direct attacks against individuals.

These figures are compiled from multiple cross-referenced sources: OIDAC reports, national police statistics, OSCE (ODIHR) records, and NGO submissions. They highlight a phenomenon that remains underreported by public institutions.

- Vandalism (62%): graffiti, overturned crosses, decapitated statues.

Examples:

- In Poland, around forty acts of vandalism specifically targeting Catholic devotion to Saint John Paul II were documented between 2019 and 2023. These included the defacement of statues, the destruction of a reliquary, the interruption of a Mass, the desecration of a consecrated host, the damage of a religious banner, the physical assault of individuals defending a monument, and even the burning of a sanctuary. The case Dariusz Czerski v. Poland, for which the ECLJ (European Centre for Law and Justice) has submitted observations, is currently pending before the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR).

- In April 2024, a 3-meter-high cross was broken in Munich (Germany) along a public Stations of the Cross trail.

- In July 2025, in Perugia (Italy), graffiti inciting violence against churches and priests was discovered on a building adjacent to San Domenico Basilica. The message read: “Churches must be burned, but with the priests inside; otherwise, it’s not enough”, accompanied by anarchist and transgender symbols.

- Since July 2025, in Münster (Germany), a church has had to remain closed outside of Mass times due to repeated vandalism since Easter: defecation inside the church, attempted arson, and the tearing down of photos of upcoming baptism candidates.

- Arson (10%): Churches set on fire, often without claims of responsibility. In France, church arson attacks increased by 30% in 2024 compared to 2023.[6]

Examples:

- In January 2024, Saint-Martin Church in Angers (France) was partially destroyed in an intentional fire.

- In January 2025, San Miguel Church in Jerez (Spain) was targeted by two arson attempts within two days.

- In February 2025, in Wurzen (Germany), two churches were set on fire.

- In July 2025, Notre-Dame-des-Champs Church in Paris (France) suffered two arson attacks within 24 hours.

- In August 2025, in Albuñol (Spain), a Moroccan national was arrested after setting fire to the Church of Santiago Apóstol in El Pozuelo.

- Threats or Harassment (8%): Anonymous letters, verbal intimidation.

Examples:

- In June 2019, Ely (United Kingdom), an evangelical pastor was harassed and threatened by LGBT activists after tweeting that Christians should not support gay pride.

- In October 2023, Langenau (Germany), a Protestant pastor received multiple threats and was assaulted after a sermon criticizing the Hamas attack on Israel. Police had to protect him during subsequent services.

- In January 2025, Siniscola (Italy), the parish priest of San Giovanni Battista, received a threatening letter against two of his parishioners.

- In July 2025, Paris (France): A Mass at La Madeleine Church was disrupted by pro-Palestinian activists.

- Physical Violence (7%): Assaults on priests, religious, or worshippers.

Examples:

- In August 2024, in Renmore (Ireland), a priest was stabbed repeatedly by a 16-year-old inspired by Daesh (ISIS) ideology.

- In November 2024, in Szczytno (Poland), a priest was assaulted by a thief inside his church and died from his injuries.

- In November 2024, in Rome (Italy), a nun was violently hit and slapped after trying to stop a man approaching the tabernacle suspiciously.

- In December 2024, in Sant’Andrea (Italy), the wine in the chalice was replaced with acid, leading to the priest’s hospitalization.

- In February 2025, outside Saint-Eusèbe Church in Auxerre (France), a Catholic priest was insulted for his faith and beaten by two attackers, who said they were “constantly bothered” by the church bells.

- Homicides (or Attempts) (2%): Murders or deadly attacks against clergy, religious, or believers.

Examples:

- On July 26, 2016, in Saint-Étienne-du-Rouvray (France), Father Jacques Hamel, 85, was slain at the altar during Mass by two jihadists.

- On October 29, 2020, in Nice (France), the Islamist terrorist attack at Notre-Dame Basilica killed a sacristan and two worshippers.

- On January 25, 2023, in Algeciras (Spain), a man attacked two churches with a machete, killing a sacristan and injuring a Salesian priest while shouting, “Death to Christians.”

- On November 9, 2024, at the Gilet Monastery near Valencia (Spain), Franciscan priest Juan Antonio Llorente was murdered by a mentally unstable man.

Most Affected Countries:

- France: 950 incidents recorded, 90% targeting churches and cemeteries. During the summer of 2025, many churches were desecrated (e.g., tabernacles broken into, feces and urine on altars), vandalized, or burned (e.g., Sierck-les-Bains, Arudy, Mortagne-au-Perche, Provins, Saint-Loup de Thillois, Pantin, La Courneuve). For the Feast of the Assumption on August 15, 2025, Interior Minister Bruno Retailleau called on prefects to remain vigilant, noting that anti-Christian acts in France had increased by 13% (401 incidents between January and June 2025, compared to 354 during the same period in 2024), and warning that Islamist terrorists are inciting attacks against Christians in Europe.[7]

- United Kingdom: 702 cases recorded in England and Wales. In June 2025, a large wooden cross was burned, and about 40 gravestones were destroyed in a major vandalism event at Saint-Conval Cemetery of Barrhead, in East Renfrewshire (Scotland).

- Germany: 277 incidents recorded, double the number of anti-Christian attacks between 2022 and 2023. The official government statistics count only politically motivated hate crimes, leaving many cases unacknowledged.

These crimes aim to intimidate believers and erase visible signs of Christianity. Despite their severity, few result in prosecutions, and the phenomenon remains widely ignored by national and European authorities.

2.2 Discrimination and Marginalization of Christians in Europe

Beyond visible violence, many Christians in Europe report experiencing more subtle forms of marginalization. These affect different areas of daily life: employment, education, public expression, media, or institutions. This phenomenon is documented by OIDAC and the 2023 UK report, The Cost of Keeping the Faith (2023), by Voice for Justice UK.[8]

According to this study, 56% of the Christians surveyed have already been mocked or rejected for expressing their religious convictions. This figure rises to 61% among those under 35. Around 18% report experiencing direct discrimination on the basis of their faith, including in the workplace. Young adults are particularly at risk in academia and other liberal professions.

Several testimonies report layoffs, refusal to hire, or harassment due to Christian positions on sensitive topics, such as abortion, marriage, or sexuality. For example, Kristie Higgs, a British educational assistant, was fired after sharing on Facebook posts critical of gender ideology. Although she finally won her case, it illustrates the growing tensions between freedom of conscience and conformity with dominant social norms.

Self-censorship is also common. Only 35% of Christians under 35 in the UK say they feel free to express their religious views in the workplace. This restraint is reinforced by the fear of being accused of engaging in “hate speech” when their moral convictions are perceived as contrary to “progressive” norms.

Finally, pro-life students in several European countries report being intimidated or excluded from academic debates. Some report having received death threats for expressing their positions.

These discriminations contribute to a progressive marginalization of Christians in the public space. They call into question not only individual religious freedom, but also the possibility of expressing convictions based on Christian tradition in a pluralistic society.

2.3 Restrictions on the religious freedom of Christians, laws and administrative deviations in Europe

Even within the European States, certain laws or administrative practices may restrict the effective exercise of religious freedom by Christians. These limitations, often indirect, affect prayer, freedom of expression, conscientious objection, or parental rights.

In recent years, several people have been prosecuted for having prayed silently in public spaces, notably around abortion clinics. In Spain, a man was arrested in May 2023 for simply praying near a medical center. In the United Kingdom, Adam Smith-Connor was sentenced in October 2024 for internally praying in a “buffer zone,” without disturbing public order.

The so-called “buffer zone” laws, adopted in the United Kingdom, Spain, and Germany, prohibit any form of presence deemed “influential” around clinics, including silent prayer. In Scotland, the law passed in 2024 even extends this ban to space visible from a private home, criminalizing the display of a simple pro-life message from a window.

Other restrictions apply to the public expression of religious beliefs. In Finland, the Christian MP Päivi Räsänen has been prosecuted since 2019 for criticizing the participation of the Lutheran Church in the events of the Helsinki Gay Pride, notably by quoting on social networks a biblical verse (Romans 1:24-27) condemning homosexual relations. In Spain, the priest Custodio Ballester faces three years in prison for having criticized Islam in a press article.

Conscientious objection is also weakened by recent legislative developments. In Germany, abortion is now integrated into mandatory medical training. In Spain, doctors must register on an official register to be able to refuse an abortion, without guarantee of respect for their choice and at the risk of being exposed to professional stigmatization. Christian establishments, meanwhile, no longer have the right to refuse to practice euthanasia.

Parental rights are challenged when Christian parents lose the right to educate their children according to their convictions. In Switzerland, a teenager was removed from her family after her parents opposed her gender change.

Finally, these political abuses also question the Christian heritage of Europe through a form of anti-Christian historical revisionism. On the one hand, this is manifested by the gradual erasure of the Christian references in public speeches (wishing for “happy end-of-year holidays” or talking about “spring vacation,” instead of “Merry Christmas” or “Easter holidays,” removing Christian holidays). In January 2011, approximately three million calendars, costing five million euros, were distributed to schools across Europe by the European Commission. The calendars mentioned Jewish, Muslim, or Hindu holidays, but, except for the Assumption of the Virgin Mary (August 15), the Christian holidays, the two most important of which, Christmas and Easter, were not indicated at all, causing many questions from MEPs. Like a final nail in the coffin of Christianity in Europe, the Assumption was translated as “the Ascension” (of Jesus Christ) in the French version of the question by Franz Obermayr (NI).

Additionally, anti-Christian historical revisionism is exercised through concrete actions of symbolic deconstruction. A striking example is found in Spain, where, under the guise of democratic memory or the fight against Francoism, we witness the systematic destruction of crosses, calvaries, and Christian symbols present in public space. Several municipalities, notably governed by the left or far left, ordered the dismantling of historical religious monuments, even when they had no explicit link with the Francoist dictatorship. Crosses erected to honor victims of the civil war or for purely religious reasons have been removed, in the name of an ideological reading of history.

This policy culminated in the questioning of the imposing cross of the Valley of the Fallen, a monumental religious site located near Madrid. This place, which houses a Benedictine abbey and a basilica carved into the rock, was originally a mausoleum wanted by Franco after the civil war. Long controversial, the site saw the body of the dictator exhumed in 2019. Now, political proposals envisage the radical transformation of the site, even the removal of the cross, more than 150 meters high, one of the largest in the world. This cross, a religious symbol rather than an ideological one for many Christians, has become the target of those who wish to erase any link between religion and national memory. The ECLJ denounced this situation in its contribution of October 2024 to the Universal Periodic Review of Spain.

All these anti-Christian shifts reveal a growing gap between the formal legal guarantees and their practical application for European Christians.

3. Understanding the Causes of Anti-Christian Hatred

3.1 Secularization, Laicism, and the Culture of Blasphemy - The Decline of Christianity in Europe

For several decades, European societies have been experiencing an advanced process of secularization. Christianity, which has long structured social, cultural, and political life, is increasingly relegated to the private sphere. This retreat is often accompanied by a form of symbolic rejection, or even contempt, for Christian traditions and values.

In many countries, Christian references are removed from the public space. Crosses are removed from official buildings, nativity scenes are prohibited in town halls, and religious processions are restricted. In April 2025, the French deputy Antoine Léaument (LFI) proposed, for example, to remove the Christian holidays from the national calendar, and in July 2025, it was French Prime Minister François Bayrou’s turn to propose the deletion of Easter Monday. These decisions are often justified by the requirement of religious neutrality, but they also reflect a desire to erase the visible signs of a Christian heritage.

At the same time, a culture of blasphemy has developed. In the media, social networks, art, and advertising, Christianity is frequently mocked. This phenomenon is part of a climate where the sacred dimension of Christianity is perceived as outdated, even ridiculous, and whose transgression does not cause fear of reprisals. Expressions of the Christian faith are often dismissed as archaic or an obstacle to progress.

Recent examples illustrate this trend. In June 2025, a Spanish comedian, who claims to have “punk humor” and whose attacks target “the police, the fascists, and the Catholic church,” simulated an act of masturbation with a cross on the altar of the church of Arbérats-Sillègue in France. During the opening ceremony of the Olympic Games in Paris in August 2024, a drag performance parodying the Last Supper of Christ was staged and broadcast live to millions of viewers worldwide.

These acts, if they do not fall within the scope of crime, contribute to a hostile climate where Christian beliefs are either ridiculed or considered undesirable in the public space. This dynamic fuels a loss of cultural legitimacy for Christianity, in favor of a model of secularism interpreted as the exclusion of all religious expression.

3.2 Who are the perpetrators of anti-Christian acts? Radical Islam, militant secularism, extreme left

Acts of anti-Christian hatred in Europe come from various ideological currents. Their common point is an explicit hostility towards Christianity as a religion, a historical legacy, or a cultural framework. Several group and individual profiles recur in cases where the motivations or profiles of the authors have been established.

- The first group identified is that of radical Muslims, often involved in cases of physical violence. In 2023, 21 documented attacks in Europe exhibited an Islamist motivation. Muslim converts to Christianity are particularly targeted, as shown in a 2021 ECLJ report. In October 2023, in the UK, a man attempted to assassinate his converted roommate, claiming he deserved to die for leaving Islam. At the end of 2024, Coptic Christians were assaulted by Muslims in a center for minors in Madrid (Spain), according to the Observatorio para la Libertad Religiosa y de Conciencia (OLRC).

- A second type of actor is made up of lay militant organizations. These groups do not satisfy their goals by defending the separation between churches and states: they actively campaign for the total exclusion of all religious expression, particularly Christianity, from public spaces. In France, the National Federation of Free Thought is taking legal action to remove crosses, statues, and nativity scenes from public places, in the name of a radical conception of secularism (statue of the Virgin at La Flotte-en-Ré, statue of Saint Michel in Les Sables-d'Olonne, cancellation of the celebrations of Sainte-Geneviève, patron saint of the gendarmes since 1962). This approach contributes to the erasure of Christian references in the common symbolic environment.

- Finally, far-left activists express ideological hostility towards Christianity, perceived as carrying conservative values, particularly those in the defense of life. In September 2023, Spanish pro-abortion activists harassed worshippers attending mass in Barcelona and inscribed offensive graffiti on the walls of the church. On October 13, 2022, the European Court of Human Rights sentenced France to pay damages and interest to a feminist activist from the collective Femen who had displayed herself topless in the Parisian church of the Madeleine in 2013, before miming an abortion and urinating on the altar steps (ECHR, Bouton v. France, 2022, see ECLJ observations). During the case of the desecrated hosts for a pseudo work of art in Spain in 2015 (ECHR, Asociación de Abogados Cristianos v. Spain, 2023, the ECLJ was party to the case on behalf of the Spanish Episcopal Conference) or again for the more than 30 degradations of statues of Saint John-Paul II in Poland between 2018 and 2023, the culprits were also far-left activists.

These different profiles share a desire to marginalize or discredit Christianity in contemporary society. Their action, although motivated by diverse reasoning, fuels a climate of hatred towards believers and their cultural or symbolic expressions.

4. What are the legal protections for Christians?

4.1 Freedom of religion at the UN, a distant protection

The United Nations Organization recognizes freedom of religion and conscience as a fundamental right guaranteed by several major texts of international law. This freedom is particularly protected by Article 18 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which is ratified by most European states. This right includes the freedom to have or to adopt a religion, to practice it individually or collectively, in public or in private, through worship, teaching, practices, and the performance of rites. It also protects the right to change religion or belief, and not to be coerced in the exercise of that right.

The UN Human Rights Committee, in its General Comment No. 22, states that this freedom is inalienable and must receive special protection, notably against any coercion by the state or third parties. It applies to all religions, beliefs, and expressions of faith, including Christianity, without any hierarchy between confessions.

The UN also protects the collective dimension of religious freedom: the right to teach a faith, to gather for prayer, to found denominational schools, or to worship in appropriate places. Any restriction to this freedom must meet strict criteria: be provided for by law, pursue a legitimate aim (security, public order, health, rights of others), and be necessary and proportionate.

Finally, the UN condemns all forms of religious intolerance. Article 20 of the ICCPR prohibits “any advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence.” Several General Assembly resolutions recall the importance of combating violence based on religion or belief. The 1981 Declaration on the Elimination of All Forms of Intolerance and Discrimination Based on Religion or Belief is a landmark in this field.

4.2 The European Union does not provide enough protection for Christians

Freedom of religion and conscience is recognized as a fundamental right by the European Union. It appears in Article 10 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, which has the same legal value as the treaties since the entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon (2009). This article guarantees everyone the right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion, including the freedom to change his religion or belief, as well as the freedom to manifest his religion individually or collectively, in public or private, through worship, teaching, practices, and the observance of rites.

This freedom is also protected by Article 9 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which the EU has promised to respect under Article 6 of the Treaty on European Union. In addition, section 21 of the Charter prohibits discrimination based on religion or belief.

The European Commission says it is “determined to combat racism, xenophobia and all forms of intolerance, including that relating to religion.”[9] Yet, in practice, only two religions benefit from a dedicated institutional mechanism: Islam and Judaism. In 2015, two European coordinators were appointed to fight against anti-Semitism and anti-Muslim hatred, respectively, within the framework of European policies to combat racism.

This difference in treatment is based on an interpretation of the religious identities concerned. Judaism is perceived as a religion, a cultural or national identity, and even an ethnic origin in certain contexts. On their side, Muslims are protected as a “race” in the name of the fight against Islamophobia.[10] This approach has gradually substituted the notion of “Muslim race” for that of “Arabs.” “Maghrebis,” “Turks,” or “immigrants,” without considering the real diversity of Muslims in Europe: European converts, black African populations, Asians, etc.

Conversely, Christians in Europe, although historically representing the majority and increasingly exposed to Christianophobia, cannot be assimilated to an ethnic or minority group. They are thus excluded from the European coordinators’ system. The only forum for dialogue proposed by the Commission remains “dialogue with churches and religious or philosophical organizations,” as provided for in Article 17 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. This imbalance in institutional recognition fuels a feeling of injustice among Christians, whose protection remains largely insufficient compared to the mechanisms in place for other belief systems.

From the outside, the European Union appears to be committed to promoting “democracy, the rule of law, the universality and indivisibility of human rights and fundamental freedoms,” including freedom of religion or belief (Article 21 §1 and §2 of the Treaty on European Union). On this basis, in 2013 it adopted Guidelines on the promotion and protection of freedom of religion or belief as part of its foreign policy, and in 2016 it appointed a Special Envoy for Freedom of Religion or Belief outside the EU. Despite some welcome initiatives, such as the participation in the liberation of Asia Bibi, this Special Envoy has an uncertain status and a budget too small to carry out effective actions. Moreover, over the ten years of existence, the position was held for only five years, often with short terms, which reflects a lack of political investment.

Regarding the internal affairs of the European Union, no equivalent provision applies. It does not currently have a specific institutional mechanism for the protection or monitoring of religious freedom in the Member States themselves. This institutional asymmetry limits the EU’s capacity to act in response to certain violations of religious freedom on its own territory.

4.3 Does the ECHR protect religions equally?

The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), a judicial body of the Council of Europe, plays a central role in protecting freedom of religion and conscience on the European continent. It monitors compliance with the European Convention on Human Rights by the 46 member states of the Council of Europe.

The main basis for this protection is Article 9 of the Convention, which guarantees everyone the right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion. This right includes the freedom to have a religion or belief, as well as the freedom to manifest it through worship, teaching, practices, and rites. This freedom has an absolute internal dimension (freedom of belief) and a relative external dimension (public manifestation), which may be subject to limitations under strict conditions (legality, necessity, proportionality).

The Court has repeatedly recalled that freedom of religion is one of the foundations of a democratic society. It protects believers against unjustified interference by the state, but also against disproportionate attacks on their religious practices. Restrictions can only be justified if they meet a legitimate objective (public order, security, health, rights of others) and are necessary in a democratic society.

Other provisions of the Convention reinforce this protection. Article 10, on freedom of expression, also applies to publicly expressed religious beliefs. Article 14 prohibits any discrimination in the enjoyment of guaranteed rights, notably on the basis of religion. Finally, Article 2 of Protocol No. 1 protects the right of parents to ensure the education of their children in accordance with their religious and philosophical convictions. The jurisprudence of the Court has established important principles on the neutrality of the State, freedom of worship, the right to wear religious symbols, conscientious objection, and even the rights of religious communities.

However, the jurisprudence of the Court reveals a differentiated approach in the protection of religions. On one hand, attacks on Christianity are generally tolerated in the name of freedom of expression, while critics of Islam are often restricted on the grounds of combating hatred. For example, in the case of Bouton v. France (2022), the Court condemned France for sanctioning a Femen activist who performed an abortion topless and urinated in front of the altar and tabernacle of the Madeleine church in Paris, considering that her criminal conviction for “sexual exhibition” violated her freedom of expression in the context of “public debate on women’s rights, more specifically on the right to abortion.”

Moreover, the claim in 2009 by a Polish singer that the Bible was the “writings of a drunk person from drinking wine and smoking weed” earned her a conviction in Poland before it was overturned by the ECHR (Rabczewska v. Poland, 2022). The Court also approved the exhibition of a painting depicting Mother Teresa and a cardinal in different sexual positions (Vereinigung Bildender Oisons v. Austria, 2007), and a wild blasphemous concert of the “Pussy Riots” in the choir of the Moscow Orthodox cathedral (Mariya Alekhina and others v. Russia, 2018).

On the other hand, many of the Court’s judgments readily analyze criticisms of Islam as “offensive attacks concerning matters deemed sacred by Muslims” (I.A v. Turkey, 2005) or “hostility towards the Muslim community” (Le Pen v. France, 2010). In the case of E.S. v. Austria (2018), an Austrian speaker who described the Islamic prophet Muhammad as a pedophile had her criminal conviction upheld by the Court, which found that her remarks constituted “incitement to religious hatred” and exceeded the permissible limits of the debate.

Similarly, the ECHR had confirmed the conviction of the French Éric Zemmour, who had stated in 2016 about the Muslims of France: “We have been living for thirty years an invasion, a colonization, which has led to a deflagration” and “I think we must give them the choice between Islam and France.” The ECtHR found that these statements reflected a “discriminatory intention likely to call upon listeners to reject and exclude the Muslim community as a whole and, in doing so, to harm social cohesion” and he was therefore a victim of censorship (Zemmour v. France, 2022).

Moreover, the Convention prohibits abuse of rights (Article 17).[11] This protects the Convention against those who would seek to use it (freedom of expression) to justify or promote behavior contrary to its fundamental principles (incitement to ethnic or religious hatred). In its thematic guide, the Court explicitly mentions anti-Semitism, Islamophobia, and hatred of non-Muslims (by Muslims) but omits any reference to Christianophobia.

5. Victims of an anti-Christian act, why and how to report it?

When an anti-Christian act is suffered or observed, it is essential to report it both to the national authorities (police, justice, institutions) and organizations that specialize in the defense of Christians and the identification of anti-Christian acts, such as ECLJ (and OIDAC Europe). It is important to clearly indicate the anti-Christian motive behind any aggression, threat, or discrimination. This clarification is crucial for accurately qualifying the facts and allowing them to be considered.

5.1 Why report an anti-Christian act?

A report first provides additional statistical documentation: many anti-Christian acts remain invisible due to a lack of reporting. The underreporting prevents the authorities from assessing the true extent of the phenomenon and delays the implementation of appropriate measures. Each report also contributes to an awareness-raising process, allowing NGOs, European institutions, or researchers to better document violations of religious freedom. The more facts are raised, the more public opinion is warned, and public decision-makers can act.

Reporting can then lead to investigation, prosecution, and in some cases, legal recognition of a religious hate crime or speech. This strengthens the protection of victims and deters perpetrators. French law, for example, explicitly recognizes that religious motivation for a crime or offence constitutes an aggravating circumstance (article 132-76 of the Penal Code).

5.2 How to report an anti-Christian act?

Several channels are available to report an anti-Christian act:

- Document facts: capture images, gather testimonials, preserve messages or publications.

- File a complaint with the police.

- Bring the case before the competent national courts if fundamental rights are unjustifiably restricted, including as a last resort to the European Court of Human Rights.

- Report hateful online content through national reporting platforms (e.g., PHAROS in France).

- Submit information to the OSCE/ODIHR by sending an incident report via email to hatecrimereport@odihr.pl, so that it can be included in the annual hate crime database.

- Alert rights defenders, labor inspections, school authorities, etc.

- Contact specialized NGOs, in the country concerned or at the European level, to identify the anti-Christian act, and benefit from legal support: ECLJ, OIDAC Europe, Observatorio para la Libertad Religiosa y de Conciencia (Spain), Laboratorium Wolności Religijnej (Poland), Commission of Inquiry into Discrimination Against Christians (UK)...

- Insisting on the anti-religious motive: in many European states, the anti-religious (especially anti-Christian) motive is recognized as an aggravating circumstance. Offences motivated by religious hatred, therefore, result in heavier penalties.

Reporting an act is not an isolated complaint; it is an act of defending fundamental rights, beneficial to the entire Christian community and society as a whole.

6. Eight concrete proposals to combat Christianophobia in Europe

The ECLJ recommends several concrete measures to strengthen the protection of Christians in Europe and to fight religious intolerance more effectively. These proposals are in line with the principles of equality, freedom of religion, and non-discrimination.

- Adopt a clear definition of anti-Christian intolerance

The absence of an official definition constitutes an obstacle to the recognition of the phenomenon. A reference definition, established at the international level, would make it possible to identify and qualify anti-Christian acts with more consistency. It would also facilitate data collection, trend analysis, and the implementation of appropriate responses by public institutions.

- Appoint a dedicated European coordinator

The establishment of a European coordinator responsible for combating anti-Christian acts would ensure an institutional point of contact for Christian communities. This role would facilitate the coordination of actions, the reporting of complaints, and the integration of this issue into European policies to combat discrimination, in line with existing arrangements for other religious groups.

- Explicitly integrate the reporting and recognition of anti-Christian acts into European texts

Acts of hatred against Christians must be recognized as a specific form of religious discrimination in the texts and strategies of the European Union. Their absence in current normative frameworks contributes to their invisibility. Formal recognition would ensure equitable protection for all religious denominations.

- Specifically identify anti-Christian acts at the national level

The creation of commissions of inquiry in the European states and a real statistical monitoring would allow for better documentation of the attacks against Christians. Collecting accurate and complete data could shed light on the rise of Christianophobia and encourage public policies to take it into account. This provides the ability, on one hand, to distinguish hate crimes from other crimes, and on the other hand, within antireligious crimes, to highlight a category specific to antichristian crimes.

- Strengthening the protection of places of worship

Many cemeteries and churches in Europe are subject to damage or desecration. The strengthening of security arrangements and applicable sanctions would better protect these places and ensure freedom of worship in safe and dignified conditions.

- Refocus legal protection on objective religious facts

The protection of religious freedom often rests on subjective notions such as “religious sentiment.” It is necessary to base this protection more on objective elements: integrity of places of worship, freedom of celebrations, and safety of the practitioners. This would allow for better legal security and a fairer balance between freedom of expression and respect for religion.

- Recognize the historical legitimacy of Christianity in Europe

The European legal framework is based on an abstract neutrality, sometimes disconnected from cultural realities. Integrating the historical role of Christianity into the formation of European societies would allow public policies to be adapted to religious diversity, without denying the continent’s religious roots. This recognition would not call into question pluralism but would strengthen social ties and mutual understanding.

- Ensuring conscientious objection in sensitive professional fields

Christians may be confronted, in certain professions, with obligations contrary to their religious convictions, notably in the fields of health, education, justice, or public service. It is necessary to legally guarantee the right to conscientious objection in these sectors. This protection must be clear, effective, and accompanied by guarantees against any form of sanction or professional discrimination.

7. Conclusion - Defending the religious freedom of Christians in the face of growing intolerance in Europe

Anti-Christian intolerance is growing in Europe, in various forms: acts of hatred, discrimination, legal restrictions, and social marginalization. This phenomenon, still too little recognized, calls into question a fundamental freedom: that of believing, practicing one’s faith, and expressing it publicly.

Freedom of religion should not be taken for granted. It deserves to be defended with rigor, for all faiths, but even more so for Christians, as it is often relegated to the background in policies to combat discrimination.

The European Union and its Member States have legal, political, and institutional tools to act. It is time to fully mobilize them to ensure fair and effective protection.

____

[1] Observatory of intolerance and discrimination against Christians in Europe (OIDAC) https://www.intoleranceagainstchristians.eu/

[2] Article 2 of the 1981 Declaration on the Elimination of All Forms of Intolerance and of Discrimination Based on Religion or Belief. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/declaration-elimination-all-forms-intolerance-and-discrimination

[3] https://www.osce.org/files/f/documents/4/a/389468_4.pdf

[4] https://eclj.org/religious-freedom/un/the-label-christianophobia-in-human-rights-law?lng=en

[5] OSCE, Understanding Anti-Christian Hate Crimes and Addressing the Security Needs of Christian Communities — A Practical Guide, July 28, 2025.

[6] https://www.lejdd.fr/Societe/les-incendies-criminels-deglises-en-hausse-de-30-en-2024-154544

[7] https://www.lefigaro.fr/actualite-france/des-actes-antichretiens-en-hausse-sur-fond-de-menace-terroriste-20250813

[8] Voice for Justice UK, The Costs of Keeping the Faith, https://vfjuk.org/resources/.

[9] https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/E-9-2021-005548_EN.html#:~:text=This%20is%20now%20being%20seen,2019%20and%202020%5B2%5D.

[10] The Council of Europe defines Islamophobia as “a specific form of racism based on prejudice or fear against Muslims and/or Islam.” https://www.coe.int/en/web/all-different-all-equal/the-shape-of-contemporary-islamophobia-and-its-specific-effects-on-young-muslims-political-and-associative-life

[11] https://ks.echr.coe.int/documents/d/echr-ks/guide_art_17_eng

Read the full PDF document