Since 2020, the ECLJ has been engaged in extremely important work to clean up the functioning of the ECHR in its relations with certain NGOs. After denouncing the existence of a structural problem of conflicts of interest between judges and NGOs, and carrying out several institutional and media initiatives, the Court finally undertook a series of internal reforms following the ECLJ's recommendations. Here is a summary of what the press has called “the Soros judges scandal.”

Introduction

The European Centre for Law and Justice (ECLJ) was founded on July 2, 1998 to act in particular before the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR). Since then, the ECLJ has intervened in more than 80 cases, representing applicants, advising governments and acting as amicus curiae. The ECLJ has thus developed an in-depth knowledge of the case law and internal workings of the European Court, and has contributed to the Court's jurisprudence in certain areas such as freedom of conscience, religion and respect for human life.

Over the years, the ECLJ has observed a growing ideological orientation on the part of the Court, diverting it from the initial inspiration of the drafters of the European Convention, and leading it to qualify as "rights" practices that were previously contrary to the Convention. It was to analyze this ideological and philosophical evolution that Grégor Puppinck, director of ECLJ, undertook the writing of the book Les droits de l'homme dénaturé, published by Le Cerf in 2018, and since translated into 5 languages.

After analyzing the evolution of the Court's case law in terms of ideas, Grégor Puppinck wished to extend this study to the sociology of the European Court, based on the idea that human rights do not only obey an internal logic, supposedly inescapable, but also political choices determined by the convictions of the judges and the dominant political orientation within the registry. The ECLJ then undertook an analysis of judges' curricula vitae over the last 10 years, covering the period 2009-2019, and was astonished to note the large number of judges who had previously been directors or employees of a small circle of NGOs and foundations. Only private organizations involved in strategic litigation at the ECHR, i.e. acting with a political aim, were included in the analysis. In a second stage, the ECLJ took the research a step further, analyzing the behavior of these judges when they were seized of cases brought or supported by the NGO from which they personally originated. Once again, we were surprised to find dozens of cases of clear and serious conflicts of interest.

After a period of hesitation in the face of the scale of the scandal, and fear of possible reprisals, and after having confidentially consulted several current and former judges of the ECHR and senior officials of the Court and of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, in charge in particular of electing judges, Grégor Puppinck decided to take the risk of publishing this report, believing it to be necessary to bring the Court to reform itself and to reduce the hold of these NGOs over the Court.

A few days before publication of the Report, entitled "NGOs and ECHR judges, 2009 - 2019", it was sent as a courtesy to the President of the Court, to the Section Presidents, and to Mr Jean-Paul Costa, former President of the Court. The ECLJ also adopted enhanced physical security measures.

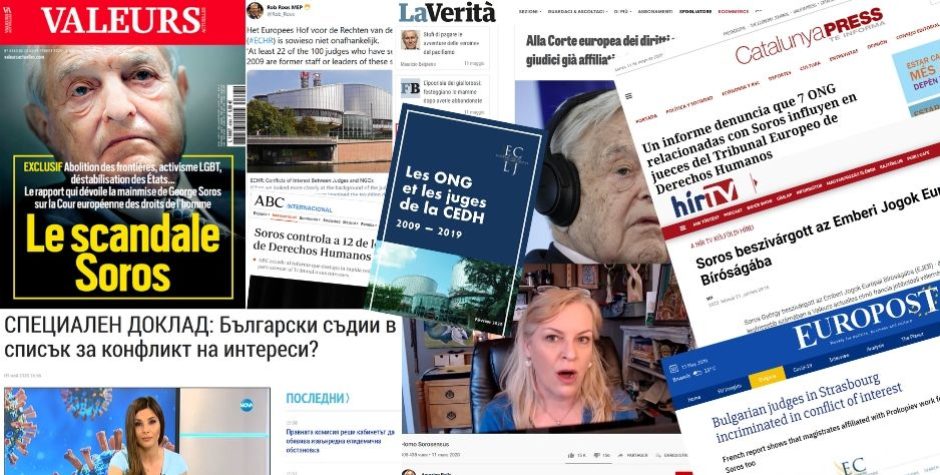

The report's publication in March 2020 triggered a wave of political and media reaction, only to be dampened by the Covid pandemic. Over a hundred articles were published on every continent. It was translated into English, Polish, Spanish, Russian, Croatian and Hungarian.

After carefully analyzing the veracity of the ECLJ report, the Court decided not to comment on it publicly, to play down its revelations to other Council of Europe bodies, and to adopt internal measures to correct the problems identified. It was also decided, at the top of the Court, not to "retaliate" against the ECLJ, as some judges and registrars considered the ECLJ report beneficial, having "opened the eyes" of the Court to some of its deficiencies.

Media reprisals were nevertheless launched, notably by the NGOs and foundations mentioned in the report. Grégor Puppinck was repeatedly advised to take care of his own safety and that of his family and friends.

In the months following publication of the report, the European Court adopted a first series of internal measures to reinforce its ethical standards.

In 2023, the ECLJ published a second report entitled "The impartiality of the ECHR - Problems and recommendations" in order to take stock of the situation, deepen the analysis and draw up a list of specific recommendations. At the same time, the ECLJ initiated a petition to the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, signed by over 60,000 people, asking it to take up this issue. As for the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe, it entrusted an intergovernmental committee of experts on the ECHR with the task of drawing up "a report assessing the effectiveness of the system for the selection and election of judges to the Court and of the means of ensuring recognition of the status and seniority of judges to the Court, and offering additional guarantees to safeguard their independence and impartiality."

Without waiting for the publication of this report by the group of experts, the European Court quickly adopted a series of measures, recommended by the ECLJ, to reinforce the independence and impartiality of its judges, in particular by adopting a procedure for recusal.

Faced with the seriousness of the scandal, the essential challenge for the European Court and the Council of Europe system was to respond rapidly to the serious problems identified in these reports, without publicly acknowledging their existence.

With hindsight, it appears that the publication of these two reports was extremely beneficial. The fact that the European Court adopted the ECLJ's recommendations is proof of the reports' validity and usefulness. They have also had the effect of significantly reducing the number of elected judges from activist NGOs active on the Court, which constitutes an improvement in the Court's system. Finally, these reports have also had the benefit of informing the general public about the workings of international institutions and the extent of the power wielded there by a few wealthy foundations and NGOs.

The following article describes in greater detail how the Court was "cleaned up".

1. Summary of the first report entitled NGOs and judges at the ECHR

In March 2020, the ECLJ published theNGOs and the Judges of the ECHR, 2009 - 2019, a summary of which follows. report

a. Acknowledgement of the presence of judges from activist organizations involved in strategic litigation at the ECHR

Between 2009 and 2019, at least 22 of the ECHR's 100 permanent judges were former founders, directors or paid staff of seven private foundations and organizations that were highly active at the ECHR as applicants, representatives or interveners. Of these 22 judges, 12 come from the Open Society Foundation (OSF) and its directly affiliated organizations, while the other ten come from organizations funded, in some cases 50%, by George Soros' Open Society Foundation. These are the A.I.R.E. Centre (Centre for Individual Rights in Europe), Amnesty International, the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ), the Helsinki Committee Network, Human Rights Watch (HRW) and Interights.

It is not forbidden for a judge to have previously worked for an NGO, but this can have consequences for his or her impartiality when that NGO campaigns for certain causes, and acts at the ECHR. Furthermore, and more importantly, the prominence of the Open Society within the Court is a fact of major political importance, and therefore deserves to be known. Revealing it is not an attack on the Court itself, but on the hold exerted by a political foundation on the Court.

b. Conflicts of interest between these judges and their former NGOs

The report goes on to analyze the behavior of the 22 judges in question when they were seized of cases brought or supported by their own NGOs, acting as applicants, representatives or third-party interveners.

Between 2009 and 2019, 185 judgments involving one of the seven identified NGOs were made public. However, on 88 occasions, 18 of the 22 judges from these NGOs judged cases brought or supported by their own organizations, thus placing themselves in a clear situation of conflict of interest. These conflicts of interest occurred in cases of sufficient importance for these organizations to feel they had to get involved; thus, 33 of these 88 cases of conflict of interest concerned Grand Chamber judgments, i.e. judgments whose jurisprudence carries the greatest authority. By way of illustration, one judge judged cases that he had potentially brought by the NGO of which he was the director and one of the lawyers at the time of the application.

c. Lack of transparency in NGO activities

An analysis of the ways in which NGOs and foundations deal with the Court has also revealed their lack of transparency.

In the absence of rules imposing minimum transparency, it is very difficult to identify all the cases in which these organizations intervene, especially when they represent the applicants without being formally mentioned. The published judgments and summaries available in the HUDOC database reflect only a tiny fraction of this reality.

This opacity is all the more problematic as some cases are strategically constructed by NGOs to influence jurisprudence. This makes it impossible to know whether the real author of the petition is the petitioner himself or the organization that accompanies him in the shadows. Only a few insiders, former NGO members or collaborators who have become judges or court clerks, are sometimes able to recognize the real players in these cases. There are also situations where the same NGO acts both as the claimant's representative and as a third party in the same case, adding to the confusion. This lack of clarity undermines the legibility of proceedings, weakens the requirement for impartiality and fuels suspicions of cross-influence between certain NGOs and the Court. Reform is therefore needed to guarantee transparency, procedural fairness and public confidence.

2. Summary of the second report on ECLJ recommendations

In 2023, the ECLJ published a second report entitled The impartiality of the ECHR - Problems and recommendations. This report deepens the analysis undertaken in 2020 on the functioning of the ECHR. It finds that cases of conflicts of interest between judges and NGOs have increased, even though the Court has adopted a number of measures to remedy the situation. The report also outlines a series of structural problems affecting the Court's impartiality, demonstrating that it is not up to the standards of other major international and national jurisdictions. In order to support the ECHR reform process, the report presents a series of recommendations aimed at resolving the problems identified.

The following is a summary of the report.

a. Persistent conflicts of interest between judges and NGOs

Between 2020 and 2022, the conflicts of interest already denounced in 2020 by the ECLJ continued at a worrying level. Whereas between 2009 and 2019, the NGOs concerned were visible in an average of 17 cases per year, this figure rose to 38 annual cases over the period studied, more than doubling. Of these 114 cases, judges sat in situations of direct conflict of interest on 54 occasions, spread over 34 cases. These judges sat while "their" former NGO was defending the claimants or intervening as a third party, which constitutes a conflict of interest. Of these 34 cases, 7 concerned Grand Chamber judgments.

In relative terms, the frequency of such conflicts decreased from 48% to 30% of cases involving these NGOs. This is mainly due to the end of the mandates of several NGO judges. In the vast majority of these 34 cases, the Court found in favor of the position defended by the NGO involved.

b. List of recommendations for the Court

The ECLJ considers that the European Court of Human Rights, as the supreme jurisdiction, must be exemplary in its respect for the principles of impartiality, transparency and competence. To preserve its authority, the ECHR should be exemplary and respect the standards it imposes on national courts in terms of the right to a fair trial, and especially in terms of impartiality. To date, this has not been the case, for a variety of reasons, the main one being that, as the supreme court, the ECHR is not subject to the control of any other court or body likely to observe its errors and malfunctions. Governments should, in principle, carry out this control, but they often feel ill-placed to do so, as any criticism of the Court coming from them may be perceived as political pressure. It is therefore up to civil society to point out these malfunctions, to assume the role of whistle-blower. This is what ECLJ has undertaken. These reforms are necessary for the good of the Court. To contribute to these reforms, the ECLJ has identified a series of measures to be implemented. These have been reviewed and approved by several ECHR judges.

They are as follows

- -Establish a challenge procedure that respects the standards the Court requires of national courts

The Court should respect the requirements it imposes on national courts in this area. In 2023, only the judge may decide to disqualify himself or herself voluntarily, which does not guarantee sufficient protection against the risk of bias. The Court could usefully draw inspiration from the procedures in force at the International Criminal Court or in several European constitutional courts, where requests for recusal are framed, reasoned and open to the adversarial process. => Recommendation adopted

- Appoint high-level judges rather than activists

The majority of ECHR judges have no experience as judges, but are former lawyers, jurists and teachers. They therefore often have an activist profile, and have not previously been subject to any obligation of reserve. They are more likely to have conflicts of interest.

- Require publication of declarations of interest

This transparency requirement is already in force within many national or European judicial institutions, such as the Court of Justice of the European Union, the French courts and the European Parliament. It is therefore logical to apply the same requirement to the ECHR, in order to identify possible conflicts of interest and strengthen public confidence.

- Check the accuracy of candidates' curricula vitae

It has come to light that some judges have not presented a truthful CV to the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe in support of their election, going so far as to usurp the titles of lawyer and lecturer.

- Avoiding nepotism

It has emerged that many judges have close family, emotional, professional or political ties with members of the government of the country from which they were elected. It would therefore be beneficial to ask candidates to reveal these links, in order to prevent favoritism, reinforce the independence of judges and strengthen respect for judicial secrecy. This problem is real, albeit discreet.

- Applying selection rules to ad hoc judges

Ad hoc judges are appointed on a discretionary basis by governments, and are therefore exempt from any selection requirements.

- Improve the transparency of NGO action before the ECHR

The ECLJ recommends that the Court require NGOs to act transparently, declaring their relations with the applicant parties when representing them or acting as third parties. => Recommendation adopted

- Ensuring registry transparency to reinforce guarantees of impartiality

The opacity of the Registry is a real problem. Unlike other international jurisdictions, the European Court does not publish a complete list of its staff, nor does it systematically communicate to the parties the identity of the agents in charge of their case. ECLJ recommends correcting this shortcoming by publishing this information, in order to guarantee balanced and transparent case handling.

- Avoid appointing the national judge as judge-rapporteur in important cases

It is common practice at the ECHR for the judge elected in respect of the State concerned to take part in the judging panel, which can reinforce the Court's legitimacy in the eyes of national public opinion. However, when he or she is appointed as rapporteur judge in sensitive cases, this can pose problems of fairness, particularly if we consider that these judges are statistically more inclined to defend their State. The ECLJ therefore recommends that this key role no longer be assigned to the national judge in important cases, or at the very least that his or her identity be clearly indicated in the judgment, as other international bodies do.

- Informing the parties of the composition of the panel before the examination

To enable claimants to exercise their right to challenge a judge, they must be informed in advance of the composition of the panel responsible for hearing their claim. At present, this information is often not revealed until after the decision, except in the case of a public hearing. This prevents the parties from effectively exercising their right to recuse themselves. This shortcoming is particularly problematic when a single judge or an ad hoc judge rules alone on a petition. This lack of transparency can undermine the right to a fair trial.

- Allowing review of a decision taken by a judge whose impartiality or independence may legitimately be called into question

According to the regulations, only "judgments" of the Court are subject to review, which excludes decisions declaring an application inadmissible, even when a party discovers a fact that could have had a decisive influence on it. The ECLJ recommends that the Court formalize the possibility of requesting a review of a case declared inadmissible, in particular when it appears that the single judge who adopted the decision in question acted in a situation of conflict of interest => Recommendation adopted

- Inform all parties of the existence of recourse to the ECHR

To date, the party who has won the case before the national courts is not informed when the case is brought before the ECHR by the opposing party, except when the opposing party is the State. As a result, only the requesting party is able to present the facts of the case to the Court, and the other party is deprived of any possibility of defending itself, or even of knowing that its interests are at stake before the ECHR.

The ECLJ therefore recommends that the respondent state be required to inform all parties concerned by the application, and that they be granted the right to intervene in the proceedings.

3. Reactions

a. In the press and media

The weekly Valeurs actuelles published a full presentation of the two reports on its front page, giving them a high coverage.

Several hundred articles have been published in Europe and around the world. Too many to mention here. For the most part, they give an objective and positive account of the report. In France, personalities such as Éric Zemmour, Michel Onfray and Gilles-William Goldnadel have mentioned the report. However, few major national newspapers initially presented the report in any detail. The newspaper Le Figaro referred to the reports on several occasions, in an objective manner.

On March 3, 2020, Le Monde published a long article attacking ad hominem the ECLJ, in reaction to the report, but without disputing its content. Samuel Laurent's article was reportedly commissioned from Strasbourg.

On March 20, 2020, Conspiracy Watch published a mediocre article offering no contradiction to the report and calling into question Grégor Puppinck's religion.

Just a few days after the publication of the first report in March 2020, the Wikipedia pages of Grégor Puppinck and the ECLJ were rewritten by a group of professionals, to discredit them. A number of lawyers and academics published articles in an attempt to damage ECLJ's reputation and discredit its reports. Examples include Martin Scheinin, "NGOs and ECtHR judges: A Clarification", published on March 13, 2020, and Laurence Burgorgue-Larsen, who falsified the conclusions of the ECLJ report in order to criticize them.

Over the years, more objective articles have been published analyzing the ECLJ's action, such as: Cliquennois G, Chaptel S, Champetier B. "How conservative groups fight liberal values and try to 'moralize' the European Court of Human Rights". International Journal of Law in Context. 2024;20(3).

b. From political figures

According to Valeurs actuelles, advisors from Matignon and the Elysée Palace phoned the weekly to inform them that they had crossed a "red line" by publishing the reports.

National political figures

Numerous politicians have made public statements, calling on their governments or the European authorities. In France, these include Philippe de Villiers, Marine Le Pen, François-Xavier Bellamy, Julien Aubert, Valérie Boyer, Xavier Breton, Bérengère Poletti, Guy Teissier, Jean-Paul Garraud, Gilles Le Breton, Nicolas Bay, Jérôme Rivière... In October 2023, Valérie Boyer asked President Macron for an inquiry into the independence of the ECHR, based on the reports of 2020 and 2023, suggesting that France's participation be suspended until an investigation was carried out.

Debates were organized in several national parliaments. These include the Netherlands, Germany and Denmark. Other debates and conferences scheduled for spring 2020 have been cancelled or postponed due to the pandemic.

Russian Foreign Minister

Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov has issued an official statement on the ECLJ report. In it, he expresses concern about the "hidden influence" of certain Western NGOs within the ECHR, and states that this influence "directly affects the quality, impartiality and fairness of the Court's judgments". Russia also believes that an "appropriate examination" of these dysfunctions by Council of Europe member states, as part of the Court's reform process, would make it possible to correct and reduce the "political interference" exerted by these NGOs in the judicial process.

The Bulgarian Minister of Justice

The Bulgarian Minister of Justice, Danail Kirilov, made a public statement indicating that the Bulgarian judge, who was severely criticized in the report, could be removed from office by the ECHR. Since then, it has been Danail Kirilov who has finally been forced to resign for having defended the independence of the Bulgarian public prosecutor.

4. Parliamentary questions and answers

Various parliamentary questions have been put by national MPs to their governments, as well as by members of the European Parliament and the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE). Here are those we have identified.

a. To the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE)

i. Written questions submitted

Between April 2020 and May 2022, six members of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) from various countries and political groups each addressed a different written question to the Committee of Ministers asking what it intended to do to resolve the problems identified in the ECLJ report. This prerogative enables parliamentarians to question the ambassadors representing Council of Europe member states on points that fall within their remit. The questions are as follows:

- Restoring the integrity of the European Court of Human Rights, Doc. 15096 24/04/2020, CM reply.

- How to remedy potential conflicts of interest of judges of the European Court of Human Rights? 15095 23/04/2020, CM reply.

- The systemic problem of conflicts of interest between NGOs and judges of the European Court of Human Rights, Doc. 15098 29/04/2020, CM reply.

- Protecting the right to challenge a judge of the European Court of Human Rights, 15260 08/04/2021, CM reply.

- Create a right to apply for review of decisions of the European Court of Human Rights, 15261 08/04/2021, CM reply.

- Requiring the publication of a declaration of interests by judges of the European Court of Human Rights, 15532 17/05/2022.

At its ministerial meeting in Athens in November 2020, the Committee of Ministers discussed this subject and adopted a declaration "calling on all those involved in the Convention to continue to guarantee the highest level of qualification, independence and impartiality of the Court's judges". It also decided to invite "the Deputies to evaluate again by the end of 2024, in the light of experience gained, the effectiveness of the current system for the selection and election of judges to the Court".

In a decision dated April 8, 2021, in response to three of the written questions referred to above, the Committee of Ministers informed the PACE Deputies of its decision adopted in Athens. It did not contest the reality of the conflicts of interest in question. It notes that "Consideration of the rules and procedures for recusal is a matter which falls within the competence of the Court in the context of the procedure for revising its Rules of Procedure". It also states that: "It agreed to examine additional means of ensuring recognition of the status and seniority of the judges of the Court, thus offering additional guarantees to preserve their independence, including after the end of their term of office" and plans to evaluate "again by the end of 2024, in the light of the experience gained, the effectiveness of the current system of selection and election of the judges of the Court."

In another decision, dated July 26, 2021, the Committee of Ministers replied to two further written questions concerning the absence of a procedure for challenging judges and the impossibility of requesting a review of the Court's decisions. While stating that it is up to the Court to resolve these problems, the Committee of Ministers informs us that "the Committee on the Working Methods of the Court is re-examining the existing Rules of Court, including Article 28". This article, entitled "Impediment, deportation or dispensation", deals in particular with the question of conflicts of interest, but makes no provision for a challenge procedure. The inadequacy of article 28 of the Court's regulations is specifically denounced in the ECLJ report, in that it makes no provision for a formal recusal procedure.

Another written question has yet to be answered. It reads as follows: "Does the Committee of Ministers intend to take steps to require the publication of a declaration of interests by judges of the European Court of Human Rights?" (Doc. 15532). The Question recalls Recommendation CM/Rec(2010)12 entitled "Judges: independence, efficiency and responsibilities", which refers to the publication of declarations of interest, and points out that members of the Court of Justice of the European Union and numerous supreme courts are required to publish such declarations of interest, as are members of parliament and the Parliamentary Assembly.

ii. Censored parliamentary questions

In the course of 2022, the Dutch President of the PACE, Tiny Kox, decided to stop forwarding to the Committee of Ministers new written questions from members of parliament relating to the judicial ethics of the ECHR. He is himself a former leader of one of the NGOs concerned by the ECLJ report. One of these questions was aimed at "guaranteeing the transparency of the composition of the ECHR's registry", by applying the same rules as those of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACtHR).

Another question censured concerns the Albanian judge Darian Pavli, and more specifically a doubt as to the authenticity of his curriculum vitae. Darian Pavli, who used to work for the Open Society in Albania and New York, presented himself as a "senior attorney" in his curriculum submitted to the Council of Europe. However, the judgments in the cases in which Mr. Pavli states in his CV that he acted on behalf of the Open Society do not mention him as an attorney. On January 9, 2022, when questioned by ECLJ, the Albanian Bar refused to indicate whether Darian Pavli had been a lawyer, citing respect for his privacy. However, it agreed to provide this information for other people. On January 19, 2022, the New York City Bar Association (home to Open Society, the organization Pavli worked for between 2003 and 2015) indicated that Darian Pavli had never been listed there. The databases of other American bars accepting foreign nationals establish that Darian Pavli is not registered with them: California, Texas, District of Columbia, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Tennessee and Washington.

On January 17, 2021, PACE deputy Barna Zigismond submits a written question to the Committee of Ministers asking whether Mr. Pavli is a lawyer. On January 18, 2021, Valérie Clamer of the secretariat of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe rejected the question on the grounds that it did not comply with the Assembly's rules of procedure.

b. Written questions put by Members of the European Parliament

i. Questions submitted

Members of the European Parliament have also addressed questions to the European Commission and Council. These include Izabela-Helena Kloc (ECR), Maximilian Krah (ID), Jérôme Rivière (ID) and Robert Roos (ECR). The European Commission replied through Věra Jourová that "The Commission has no doubts about the integrity and independence of the European Court of Human Rights." The European Commissioner, Johannes Hahn, completed this response in a lapidary fashion. As for the European Council, it declared that it had no business commenting on an NGO report. When these responses were published, it became clear that Open Society had the explicit support of Commissioners Hahn and Jourová, the latter declaring, while posing alongside Mr. Soros, that "Open Society's values are at the heart of the EU's action". Johannes Hahn, also posing with George Soros, declares that "it is always good to meet George Soros to discuss our joint efforts to accelerate reforms and open societies in the Balkans and Eastern Europe". Between 2014 and 2018, George Soros and his lobbyists benefited from no fewer than 64 meetings with senior Commissioners and officials of the European Commission, a considerable number, according to the Commission's transparency register.

ii. Censored questions

On October 10, 2023, Nicolas Bay, Member of the European Parliament, sent a written question to the European Commission asking whether Mr. Pavli was a lawyer. Nicolas Bay did not receive a reply from the Parliament's services; his question was never published and was probably deleted in violation of the European Parliament's rules of procedure.

In January 2024, Jean-Paul Garraud sent a new written question to the European Commission on this matter. On January 26, 2024, the services of the European Parliament asked him to amend it so as not to target Mr. Pavli, on the grounds that it would not comply with data protection rules. However, many of the questions mention individuals by name.

c. Questions from national parliamentarians

Written questions have been submitted by members of parliament from Austria, Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands. In France, MP José Evrard put a question to the government, which replied by reminding him of the rules governing the appointment of judges to the ECHR. In Switzerland, Councillor Jean-Luc Addor asked the Federal Council about the ECLJ report. The Council, like the other public authorities questioned, failed to reply on the subject of conflicts of interest, confining itself to recalling, for the most part, the procedure for appointing judges, and considering it beneficial that some of them come from NGOs.

5. ECLJ petition to PACE

On October 12, 2022, a petition entitled "Putting an end to conflicts of interest at the ECHR", signed by over 60,000 European citizens, was submitted to the President of PACE, under article 71 of its Rules of Procedure, in view of PACE's central role in the evaluation and election of ECHR judges. The petition calls on the Parliamentary Assembly to place this issue on its agenda, so that a report can be drawn up and solutions recommended to the Committee of Ministers. The admissibility of the petition was to be examined by PACE's Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights, before being considered on its merits.

The petition sets out a list of measures that should be recommended to the Court, including :

- requiring judges to publish declarations of interest ;

- require candidates for the office of judge to declare any family ties with a member of their national government or parliament;

- avoid the presentation of candidates from militant organizations active at the ECHR;

- establish a formal challenge procedure, in line with the Court's requirements for national courts;

- inform the parties in advance of the composition of the bench, out of respect for judicial transparency, and to enable the parties to request the disqualification of a judge;

- make it mandatory, rather than optional, for judges to inform the President of the Court in the event of any doubt as to their objective independence or impartiality;

- draw up an application form for third-party intervention, indicating any links with the main parties;

- ensure PACE control over the choice of ad hoc judges;

- increase transparency in the operation of the Expert Advisory Panel on candidates for election as judges to the Court;

- publish the list of members of the Court's registry, as the Inter-American Court of Human Rights and the Court of Justice of the European Union do.

The PACE secretariat was surprised by the scale of the petition, given its technical nature and the public's lack of interest in PACE. The PACE Bureau did not reject the petition out of hand, and referred it to the Legal Affairs Committee for an opinion.

This Committee held a lively debate on the petition, on a confidential basis, and adopted a confidential position addressed to the Bureau. Mr. Puppinck has read out this communication, which states in substance:

"the petition raises a serious issue, it is preferable that PACE does not follow it up publicly so as not to damage the Court's reputation; the Court is committed to a process of internal reform to address the issues raised by the petition. Let's wait and see how this internal process evolves. If the Court does not adopt the necessary reforms, PACE could take up the issue.

On this basis, the Bureau of the Assembly rejected the petition without providing any official explanation to the signatories.

In parallel with this petition, a motion for a resolution entitled The serious problem of conflicts of interest at the European Court of Human Rights (Doc. 15661) was tabled on

November 31, 2022 to the PACE by twenty parliamentarians from fourteen member countries of the Council of Europe. The fate of this motion for a resolution was linked to that of the petition. It was forwarded by the PACE Bureau to the same Committee "for information as part of the examination of the admissibility of the petition received on the same subject". The rejection of the petition led to the rejection of the motion for resolution.

6. Reactions from legal experts

In May 2020, more than a hundred jurists, legal professionals, academics and national judges, including members of national supreme jurisdictions and a former member of the ECHR, published a collective tribune "for the independence and impartiality of the ECHR" expressing their concern at situations of conflict of interest at the ECHR, and calling on the Court to take the necessary steps to remedy the situation.

7. Creation of the group of experts on the Court's judges

On July 11, 2022, following the decision of the Athens ministerial meeting of November 2020, the Steering Committee for Human Rights (CDDH), which leads the Council of Europe's inter-governmental work in the field of human rights, set up a Drafting Group on issues relating to judges of the European Court of Human Rights (DH-SYSC-JC) with a mandate to prepare, before December 31, 2024, a "report assessing the effectiveness of the system of selection and election of the Court's judges and the means of ensuring recognition of the status and seniority of the Court's judges, and offering additional guarantees to safeguard their independence and impartiality".

The phrase "and offering additional guarantees to safeguard their independence and impartiality" addresses the issue of conflicts of interest. This is the most important institutional consequence of the ECLJ report.

Grégor Puppinck participated in the work of this committee as a representative of the Holy See.

This Drafting Group acted in coordination with the European Court to give it the initiative and time to amend its Rules with a view to strengthening the guarantees of impartiality of its judges. The Group published its report "[n]oticing that the process of modification by the Court of Rule 28 of the Rules of Court is progressing". This approach enabled the Drafting Group and the CDDH to avoid publicly denouncing the Court's shortcomings in this area, and to take note of its progress.

It is worth noting the extremely virulent attitude of German expert Hans-Jörg Behrens, elected to chair the Group, who did his utmost to avoid talking about conflicts of interest, and is directly opposed to the simple reference to "declarations of interest".

On December 1st2023, the Council of Europe's Steering Committee for Human Rights CDDH adopted the Report on "Questions relating to ECHR judges".

8. The Court's response

According to the newspaper Le Monde, although the report provoked the "anger" of the ECHR, the latter decided not to react publicly, and not to respond to the press, after verifying and noting the accuracy of the facts set out in the report.

a. Public responses from ECHR Presidents

The President of the ECHR did, however, have to answer questions put by members of the PACE and the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe on the ECLJ reports.

On April 22, 2020, during an exchange of views between the Committee of Ministers and Mr. Linos-Alexandre Sicilianos, then President of the ECHR, the latter was questioned by the Russian ambassador on the report, supported by his Turkish counterpart. President Sicilianos did not contest the report, but sought to limit the Court's responsibility, pointing out that the existence of judges from NGOs was the fault of the States, which were responsible for proposing candidates for the position of judge. He would not have denied the cases of conflicts of interest, but tried to put them into perspective in view of the thousands of cases judged each year by the Court.

Later, the Court reportedly refused to respond to a request for information issued by the secretariat of the Committee of Ministers, asking for its assistance in answering written questions put by members of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe.

On November 20, 2020, Mr. Robert Spano, Mr. Sicilianos' successor as President of the ECHR, was in turn questioned during an exchange of views with the PACE. Asked specifically about the issue of conflicts of interest, he replied on the link between judges and NGOs, but without mentioning the central question of conflicts of interest. Indeed, he declared:

I'll give you the same answer that I gave and that my predecessor gave to the Committee of Ministers in May. In our view, there are no credible allegations of influence by non-governmental organizations on the work of the Court. Some of the Court's judges have, in their previous professional lives, had experience of, or received training in, human rights law through work in non-governmental organizations. This shows the diversity of their professional backgrounds, which is essential for an international court. But the key point is that it is the Parliamentary Assembly that elects the judges. The Curriculum Vitae of the judges, with all their professional background and experience, is submitted to the Parliamentary Assembly when it elects the judges. So it's up to you to decide on the diversity of the group of judges who sit on the Court. I personally do not accept, and I say so very clearly, the allegations that have been made, and on this point I do not vary from the opinion of my predecessor Alexandre Sicilianos.

It should be remembered that the main problem highlighted by the report was not that judges had worked for NGOs prior to their election, but that they sat on cases in conflict of interest with these NGOs. President Spano has no answer to this question.

b. Reforms implemented by the Court in line with ECLJ recommendations

i. Revision of standards of judicial ethics

On September 2, 2021, the ECHR published a revised version of Resolution on Judicial Ethics its adopted on June 21, 2021. This is a document drafted by the Court which sets out its rules and the ethical obligations of judges. The previous text dates from 2008; comparing it with the new text, it appears that the revision is profound and partially addresses the issues raised by the ECLJ report. The new text reinforces judges' obligations of integrity, independence and impartiality. Echoing the ECLJ report, the resolution now obliges judges to be independent of any institution, including "any organization" and "any private entity", in reference to NGOs and other foundations. The text adds that judges "shall be free from any undue influence, whether internal or external, direct or indirect. They shall refrain from any activity, comment or association, refuse any instruction and avoid any situation that could be interpreted as detrimental to the exercise of their judicial functions or as likely to undermine the confidence that the public must have in their independence". The previous text was much more succinct.

On the subject of impartiality, the new text adds an explicit prohibition on "participating in any matter that could be of personal interest to them", thus reinforcing the prevention of conflicts of interest. Judges must also refrain from "any activity, comment or association that could be construed as undermining the public's confidence in their impartiality".

The Court's new Resolution on Judicial Ethics also places a new obligation on judges to be diligent in their duties as judges, to limit their outside activities, and most significantly, to refrain from criticizing the Court, through a new prohibition on "expressing themselves, in any form or by any means, in a manner which would be detrimental to the authority or reputation of the Court, or which would be likely to give rise to reasonable doubts as to their independence or impartiality". This applies in particular to untimely public statements by judges on matters under consideration by the Court. Another new prohibition concerns the acceptance of "any decoration or award during the performance of their duties as judges of the Court". This follows the scandal caused by the acceptance by the President of the Court of an honorary doctorate in Turkey in September 2020.

ii. Clarification of the modalities of intervention by NGOs and third parties

On March 20, 2023, the European Court of Human Rights published a revised version of its Rules, to which it appended a new "Practical Instruction" on third-party intervention. Taking up recommendations made in the ECHR's NGOs and Judges report, the Court now significantly requires any application for third-party intervention to contain "sufficient information on: a) the potential intervener; b) any link existing between that potential intervener and the parties to the proceedings; c) the reasons why the potential intervener wishes to intervene". The ECLJ had exposed the lack of transparency of many interventions and asked "[to] draw up an application form for intervention in which the natural or legal person applying to intervene should declare his or her interests, [...] as well as any links with the parties, in particular if they are acting in concert."

ECLJ welcomes the publication of this practical instruction, but notes that other problems remain. For example, it is regrettable that the Court has not taken the opportunity to make another important improvement to the system: to provide for the obligation to inform third parties interested in a case brought before it, and to guarantee them the right to intervene. These may include, for example, "the applicant's adversary in the domestic civil proceedings giving rise to the individual application before the Court, or [the] other parent in child custody cases." The rights and interests of such persons may in fact be directly affected by the Court's judgment; and it would be right for them to be involved in the proceedings.

In its Practice Direction, the Court recognizes that for these interested third parties, "'the interests of justice' may require that they be heard before the Court rules on a question likely to affect their rights, even indirectly." But these interested third parties would have to be informed of the existence of the appeal. At present, this is not the case. As a result, the Court often rules without hearing the arguments of these people, without allowing them to defend themselves.

This is a structural flaw in the procedure at the ECHR which deserves to be corrected, even if it means a small additional workload for the Court.

Secondly, the third-party intervention procedure would be less arbitrary if the Court had imposed on itself the obligation to justify its decisions rejecting applications to intervene.

iii. Revision of the Rules of Court relating to impartiality

α. Creation of a challenge procedure

On December 15, 2023, the European Court substantially amended Article 28 of its Rules, which is now entitled "Impediment and challenge". It finally institutes a procedure for the disqualification of judges, a procedure which did not previously exist, in line with the ECLJ's request.

Article 28, "Impediment and disqualification", reads as follows:

- Every judge is bound to sit in all cases assigned to him unless, for one of the reasons set out in paragraph 2 of this article, he is unable to take part in the consideration of the case.

- No judge may take part in the consideration of a case :

- a) if he has a personal interest therein, for example by reason of a marital or parental relationship, other close family relationship, close personal or professional relationship, or a subordinate relationship with any of the parties ;

- b) if he has previously intervened in the case, either as agent, counsel or adviser to a party or to a person with an interest in the case, or, at national or international level, as a member of another jurisdiction or commission of inquiry, or in any other capacity ;

- c) if, while he is an ad hoc judge or a former elected judge continuing to sit under article 26 § 3 of these Rules, he engages in any political or administrative activity, or in any professional activity incompatible with his independence or impartiality;

- d) if he has expressed opinions in public, through the media, in writing, by public actions or by any other means, which are objectively such as to prejudice his impartiality;

- e) if, for any other reason, his independence or impartiality may legitimately be questioned.

- Any judge who, for one of the reasons set out in paragraph 2 of this article, considers himself prevented from sitting in a particular case in which he has been called upon to participate must, as soon as possible, in the case of a case assigned to a committee or chamber formation, notify the president of the section, who will decide whether that judge should be excused from sitting. In the event of doubt on the part of the judge concerned or the Chairman as to the existence or otherwise of one of the grounds for dispensation listed in paragraph 2 of this article, the Chamber shall decide. It shall hear the judge concerned, then deliberate and vote without his presence. For the purposes of the deliberations and vote in question, the judge concerned shall be replaced by the first substitute judge of the Chamber. The same applies if he is sitting in respect of any Contracting Party under Articles 29 and 30 of these Rules.

- Only the parties to the proceedings may, for one of the reasons set out in paragraph 2 of this article, request the disqualification of one of the judges called upon to sit in the case in question. Any such request must be duly substantiated and submitted as soon as possible after the author has become aware of the existence of such reasons. The Chamber shall decide on the request in accordance with the procedure set out in paragraph 3 of this article. The parties shall be informed of its acceptance or rejection.

- The above provisions shall apply, mutatis mutandis, to cases brought before the Grand Chamber, and - under the authority of the President of the Court - to judges called upon to sit as single judges under article 27 of the Convention or as permanent judges under article 39 of these Rules.

The Court has supplemented Article 28 of its Rules by publishing a four-page "practical instruction" appended to its Rules, setting out the procedure for challenging judges.

The Court has also adopted two additional ECLJ recommendations, one aimed at enabling applicants to know in advance the identity of the judges likely to decide their case, and the other formally clarifying the possibility of requesting the reopening of a case after a decision of inadmissibility. Such a possibility is necessary in the event that the petitioner finds that a judge who issued the inadmissibility decision had a conflict of interest. These are significant improvements to the way the Court operates.

β. Creation of a Council of Ethics to advise the President of the Court

On December 16, 2024, the Plenary Court of the ECHR decided that its President would henceforth be able to consult a Council of Ethics whenever he or she considered it necessary to give a judge who so requested guidance on compliance with ethical standards in a given situation. The Ethics Council is competent to give guidance concerning sitting judges, ad hoc judges and former judges. Guidance may also be given concerning the Court itself as an institution. The Ethics Council is made up of five members: the longest-serving Vice-President of the Court, the longest-serving Section President and the three longest-serving judges. The Ethics Council will be assisted by the Registrar of the Court.

9. Effects on the subsequent composition of the Court

Since the publication of the 2020 report, the number of judges from NGOs active at the ECHR has fallen significantly, with several having completed their terms and others not having been elected. This is notably the case for Belgian candidate Maïté De Rue, a jurist employed by the Open Society Justice Initiative in New York since 2018, who failed to be elected, despite being the favorite, in April 2021.

Conclusion

Five years after the scandal caused by the publication of ECLJ's first report, much has been achieved. In an April 9, 2025 resolution entitled "Respect for the rule of law and the fight against corruption in the Council of Europe", the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe "welcomes the steps recently taken by the European Court of Human Rights to review and make more transparent its own procedures and ethical standards, including with regard to recusal. The Assembly encourages the Court to foster the development of an ethical culture and to monitor ethical issues closely."

A number of improvements and reforms are still needed in the procedure for selecting and electing judges, and in the way the Court operates.

In particular, the Court's registry needs to be reformed, to make it less opaque and more independent, in line with other major international jurisdictions.