Article 7 of the Treaty on European Union and the protection of the "values of the Union": legal tool or political weapon?

Article 7 of EUTreaty: Tool or weapon?

A guest post by Jérôme Soibinet.

The European Union institutions are regularly at the forefront in politics and even more so in the media when they attack such or such government of a Member State for what they consider to be human rights abuses, or "serious violations of the Union's values". Looking at the targeted countries and those that are never targeted, one may wonder about the real motives behind these concerns and even more so about the legitimacy of these institutions to impose their own interpretation of vaguely defined values upon the States that created them?

For, at the beginning of the construction, there was no real question of values or human rights, and it was only gradually that these notions were added.

In its current version, Article 2 of the Treaty on European Union states that “The Union is founded on the values of respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and respect for human rights, including the rights of persons belonging to minorities. These values are common to the Member States in a society in which pluralism, non-discrimination, tolerance, justice, solidarity and equality between women and men prevail.”

However, in its original version, the Treaty of Rome was essentially economic in nature and scope and did not include any clause relating to these 'values' as they are understood today. Thus, in the original Treaties, equality mainly concerned equality of remuneration, the only rights mentioned being almost exclusively 'customs' or 'excise' duties, and freedom was not general but concerned above all the freedom of establishment of nationals of one Member State in the territory of another, followed by freedom of capital movements and freedom of movement for workers. The six founding States of the European Economic Community then relied on a form of mutual trust in their individual operation in these areas. In case of doubt or even disputes, they relied on the judgements of the European Court of Human Rights, which was set up in 1959 to rule on individual or State applications alleging violations of the civil and political rights set out in the 1950 European Convention on Human Rights, to which said founding States are signatories.

However, it was another court that set in motion the process that gave rise, inter alia, to the fundamental rights framework that we know today. Thus, as early as the 1960s, the Court of Justice of the European Communities (CJEC), which has since become the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) under the Maastricht Treaty, developed a body of case law that gradually established the institutional and legal framework for relations between the Union and the Member States, in which “The transfer by the States from their domestic legal system to the Community legal system of the rights and obligations arising under the Treaty carries with it a permanent limitation of their sovereign rights, against which a subsequent unilateral act incompatible with the concept of the Community cannot prevail.” (ECJ, Case 6/64 - Costa v. Enel).

The European Court then extended this case law to human rights. Considering it its task to ensure the respect for the fundamental rights, which, based on the constitutional traditions common to the Member States, must be understood within the framework of the structure and objectives of the Community; thus, “the validity of a community measure or its effect within a member state cannot be affected by allegations that it runs counter to either fundamental rights as formulated by the constitution of that state or the principles of a national constitutional structure” (ECJ, Case 11/70, Internationale Handelsgesellschaft mbH).

At the same time, the European institutions have gradually acquired instruments to define their own legal and political corpus regarding human rights. This process was formally completed with the adoption by said institutions, on 7 September 2000, of the Charter of Fundamental Rights, but even more so by its formal annexation to the Treaty of Lisbon signed on 13 December 2007, thus giving it a binding legal force equivalent to the latter. Also noteworthy is the creation in 2007 of an EU agency for fundamental rights which aims to "instil a fundamental rights culture across the EU" (which probably did not exist before...), and the establishment in 2014, by the European Commission of a " A new EU Framework to strengthen the Rule of Law" (COM(2014)158 final) which “provides guidance for a dialogue between the Commission and the Member State concerned to prevent the escalation of systemic threats to the rule of law […] in order to prevent the emergence of a systemic threat to the rule of law that could develop into a 'clear risk of a serious breach' which would potentially trigger the use of the 'Article 7 TEU Procedure'.” The unelected Commission is self-proclaiming with this tool to be an 'expert in fundamental rights' and to be the sovereign judge of the legitimate governments of the Member States towards no less than “systemic threats to the rule of law”.

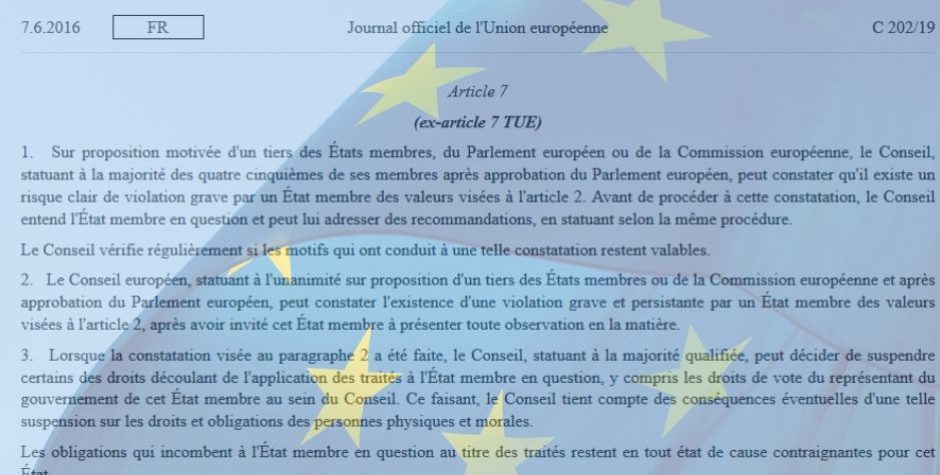

Within this general framework of fundamental rights, the Treaty of Amsterdam therefore inserted Article 7 TEU, which provides for a specific mechanism via a ‘preventive’ phase to ensure that there be no “serious and persistent breach by a Member State of the values [of the Union]”, and a 'repressive' phase if such a breach be established. Thus, on the basis of this mechanism and the wide range of rights it covers, the Brussels institutions have a monitoring tool which goes beyond the powers conferred on them by the Treaties and gradually extends to all the "values of the Union”. The vague content of the latter allows for a broad interpretation, particularly in the light of the no less vague "spirit of the Treaties".

In both phases of this procedure, however, the Council has reserved a 'way out' for itself since, in the first case, it “The Council shall regularly verify that the grounds on which such a determination was made continue to apply”, implying that, if necessary, it may lift the procedure, and in the second, it may decide subsequently to vary or revoke measures taken under paragraph 3 in response to changes in the situation which led to their being imposed.” In any event, the power remains to the States to assess, both upstream and downstream, the relevance of the procedures envisaged or initiated.

The 'preventive' procedure was the one triggered by the Commission against Poland in 2017, and by the Parliament against Hungary in 2018. However, the media coverage created by the implementation of these procedures seems to be at odds with the results. In fact, the triggering of Article 7 against Poland, for example, has led to three hearings of the Polish government before the General Affairs Council. At each hearing the Polish delegation made a presentation, after which the national representatives had the opportunity to ask two questions to the Polish delegation. Virtually no Central or Eastern European countries took the floor at these hearings, including Austria, which held the Presidency of the Council at the time, the questions coming mainly from 'Western' governments and the Scandinavian countries. This division reflects the political split lines that exist on this issue, and the little interest shared within the Council about this procedure. Indeed, it will have escaped no one's notice that such power left in the hands of the European institutions can be turned against any Member State at the whim of political movements, either within the States or within the institutions themselves.

Through these tools implemented in the infinite field of "fundamental rights" and the "values of the Union", both the European Commission and the CJEU are moving from a legal examination to a teleological interpretation, from a control mission to an eminently political dimension. They are therefore not only, respectively, the 'guardian of the Treaties' and the guarantor of the homogeneous application of the law, but even more so and above all as advocates of what increasingly appears to be the supranational constitutional nature of the Union. For the CJEU, the integrity of Union law can only be ensured on the almost express condition that it retains an absolute monopoly on the interpretation of this law, and more broadly on the exegesis of the "spirit of the Treaties". It is therefore no longer the Member States which, as holders of sovereignty in international law, have a general competence, also called 'competence of competence', which they can delegate to a cooperation body, but a new constitutional order in which the said body would become the master of competence, defining the rules which States only have the power to implement. The Member States remain legally the holders of sovereignty and politically the frameworks of democratic life but, in the name of the "values of the Union" and the "spirit of the Treaties", they are gradually being defeated in favour of the European institutions. In the name of fundamental rights, what Jacques Delors himself described, in a 1999 speech in Strasbourg cathedral, as "a technocratic looking construction progressing under the aegis of a kind of gentle and enlightened despotism", imposing, under the pretext of very general values, the political vision of oligarchic institutions on the democratically elected leaders of sovereign states, has thus been developed from the outset. In the end, the " systemic threats to the rule of law " and of democracy may not be where one would think....