About the case of Sekmadienis Ltd. v. Lithuania

On January 31st, 2018, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) published a chamber judgment in the case Sekmadienis Ltd. v. Lithuania (n°69317/14) about commercial advertisements attacking Christianity and public morality. The Court considered that the Lithuanian domestic courts, by condemning the clothing company to a fine, had violated its right to freedom of expression.

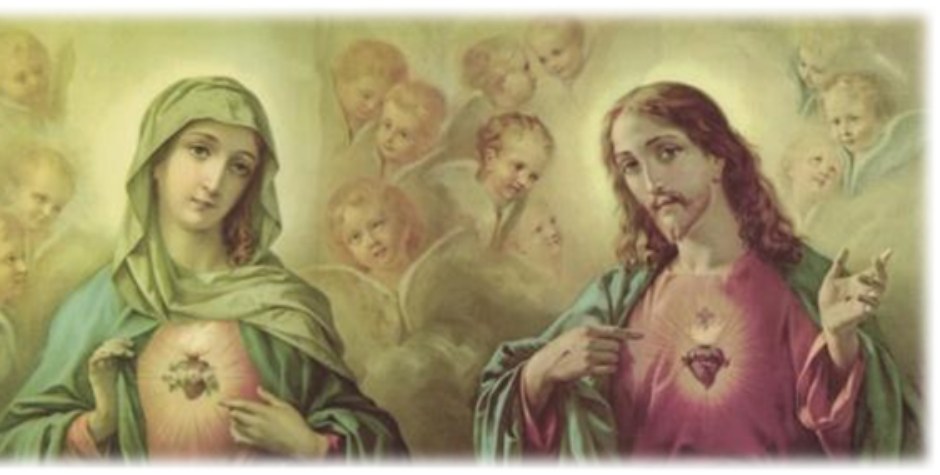

The contentious advertisements, broadcast in September and October 2012, depicted Jesus dressed in jeans and the Virgin Mary dressed in a white dress, each with tattoos. The State Consumer Rights Protection Authority (SCRPA), after receiving complaints, asked a commission for advertising regulation to give an opinion on the advertising campaign. This commission of experts considered that the advertisements could be seen as humiliating and degrading and that they "[could] really offend religious people." Its recommendation was to remove these advertisements and to "have regard for the feelings of religious people [and] to take a more responsible attitude towards religion-related topics in advertising." (§ 11) This opinion, followed by other complaints, led the State Inspectorate of Non-Food Products to examine the advertisements and to consider that they violated the Lithuanian Law on Advertising by being contrary to public morals. The company Sekmadienis Ltd. contested this conclusion, stating in particular that "the people depicted (...) could not be unambiguously considered as resembling religious figures" and that "the interests of one group – practising Catholics – could not be equated to those of the entire society."(§ 14) Not convinced by these arguments and after further consultations, including the Catholic Church, the SCRPA fined the clothing company.

Sekmadienis Ltd. sued the SCRPA and continued to assert that "the persons and objects shown in the advertisements were not related to religious symbols" (§ 20), that they were therefore not offensive to religious people and that its right to freedom of expression had been violated. The domestic courts considered that the restriction on freedom of expression decided by the SCRPA was legal and justified. After having exhausted all domestic remedies, the clothing company lodged an application with the ECHR, invoking Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which enshrines freedom of expression.

The parties and the ECHR agreed that the fine imposed on the applicant company because of its advertisements is a restriction on freedom of expression (§ 62), and that this restriction did pursue legitimate aims (§ 69). These are the protection of morals, arising from the Christian faith shared by 83% of the population,[1] and the "right of religious people not to be insulted on the grounds of their beliefs" (§ 69). It is on the assessment of the "necessary" nature of the interference "in a democratic society" that the applicant company and the Lithuanian Government disagree.

Was the interference necessary to protect the right of religious people and morals?

The adjective "necessary" in Article 10-2 of the European Convention refers to the existence of a "pressing social need." (§ 71) The extent of the margin of appreciation left by the ECHR to States to assess the existence of such a need depends on the circumstances. In the present case Sekmadienis Ltd. v. Lithuania, many elements broaden the margin of appreciation left to the Lithuanian State.

Given that morals and religion are sociological and evolving data for the European Court, detached from the search for good and truth, the national authorities are the most capable of judging them. The ECHR confirms the decision Handyside v. United Kingdom of December 7th, 1972[2] by explaining that States enjoy wide discretion in regulating freedom of expression when "intimate personal convictions" about morals or religion are offended (§ 73).

In addition, and above all, advertisements are commercial and therefore by their nature aim to arouse emotion to trigger a purchase and increase the turnover of a company. As the European Court acknowledges, the applicant company had thus no intention to "contribute to any public debate concerning religion or any other matters of general interest" (§ 76). The judgment of Markt Intern Verlag GMBH and Klaus Beermann v. Germany of November 20th, 1989 shows that the national margin of appreciation is broader in economic matters, in particular for commercial advertising.[3]

In spite of all these circumstances, the national margin of appreciation is never unlimited and the ECHR has made its own assessment of the necessity of the interference taking into account several factors.

According to the European Court, advertisements would be "gratuitously offensive" to religious people neither by themselves nor because of the circumstances (§ 77-78). Although 77% of the Lithuanian population belongs to the Catholic Church[4], the ECHR has set aside the opinion of the Lithuanian Bishops Conference of March 5th, 2013. The bishops had indeed considered, after receiving complaints from Catholic citizens, that these advertisements "[offended] the feelings of religious people."

The Court then considered that the advertisements displayed do not incite hatred based on religion and do not attack a religion “in an unwarranted or abusive manner.” (§ 77) In fact, the positions, clothing and words of the characters of Jesus and Mary on advertisements do not seem to have such an objective.

With regard to the protection of morals, the ECHR considered that the Lithuanian domestic courts had not stated "relevant and sufficient reasons" to justify a restriction on the freedom of expression. Yet their argument seems quite satisfactory. According to the Lithuanian Supreme Administrative Court in its decision of April 25th, 2014, "advertisements (...) are clearly contrary to public morals, because religion (...) unavoidably contributes to the moral development of the society." Moreover, "symbols of a religious nature occupy a significant place in the system of spiritual values of individuals and the society, and their inappropriate use demeans them [and] is contrary to universally accepted moral and ethical norms." (§ 25) According to the Lithuanian Bishops Conference, “Christ and Mary, as symbols of faith, represent certain moral values and embody ethical perfection, and for that they are examples (...). The inappropriate depiction of Christ and Mary in the advertisements encourages a frivolous attitude towards the ethical values of the Christian faith, and promotes a lifestyle which is incompatible with the principles of a religious person.” (§ 16)

The European Court could have taken greater account of this link between religion and morals in Lithuanian society, because it is unquestionable "sociological data."

The reasoning of the ECHR has weaknesses on two points used to reject the position of the Lithuanian domestic courts.

Firstly, the European Court considered that the Lithuanian domestic courts and authorities should have proven what appears to be obvious facts. In particular, they should have shown, according to the Court, that "Jesus" and "Mary" are indeed religious references and are not used only as emotional interjections (§ 79). Yet there are several visible elements that clearly show that "Jesus" and "Mary" unquestionably refer to the Biblical characters. It is for instance possible to distinguish a rosary, halos and nimbuses, two Christian crosses, a tattoo representing the pierced Immaculate Heart of Mary and a crown evoking the crown of thorns.

Secondly, the ECHR criticized the domestic courts for not having consulted both Christian non-Catholic and non-Christian religious communities (§ 80). The former represent only 5.7% of the population and are mainly composed of Orthodox Christians,[5] who also worship the Virgin Mary. The latter represent less than 1% of the population, do not recognize Jesus as God and Son of God, and do not give to his mother Mary the same importance as in Christianity. It does not therefore seem relevant to consult them.

The impact of advertising on the public morality of the Lithuanian society has been underestimated, given the strong links between religion and morals in this predominantly Christian country. This decision, which justifies immorality in the name of freedom, could be perceived by Lithuania as discrediting human rights.

The ongoing work of the Council of Europe and the United Nations on freedom of expression and freedom of religion

The judgment Sekmadienis Ltd. v. Lithuania should be read in the light of the ongoing work of the Council of Europe and the United Nations (UN) on freedom of expression and freedom of religion.

The Drafting Group on freedom of expression and links to other human rights, belonging to the Steering Committee for Human Rights (CDDH), was set up to reflect on the freedom of expression in the context of "culturally diverse societies." In January 2018, the mandate of this group of experts (CCDH - EXP) was renewed for two years by the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe.[6] In July 2017, the CCDH - EXP published an analysis of the jurisprudence of the ECHR on freedom of expression.[7] This report may be considered together with the one submitted to the UN Human Rights Council on December 23rd, 2015 by the Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief. Heiner Bielefeldt devoted this thematic report to the relationship between the right to freedom of religion or belief and the right to freedom of opinion and expression.[8]

According to the report of the CCDH - EXP, the "duties and responsibilities" of those who exercise freedom of expression seem to have a weaker weight in the recent jurisprudence of the European Court.

The jurisprudence of the ECHR usually takes into account these "duties and responsibilities." In the field of religion, according to the report of the CCDH - EXP, people have an "obligation to avoid as far as possible expressions that are gratuitously offensive to others and thus an infringement of their rights, and which therefore do not contribute to any form of public debate capable of furthering progress in human affairs.”[9] In its case-law, the European Court thus tends to "[make] a clear distinction between information (facts) and opinions (value judgments), as the dissemination of the former enjoy very strong protection."[10] Similarly, it distinguishes "between criticism and insult"[11]. In the decision Otto-Preminger-Institut v. Austria of September 20th, 1994, despite the "merit [of the film] as a work of art" and its "contribution to public debate," the Court agreed with the Austrian authorities who "in seizing the film (...) acted to ensure religious peace in that region and to prevent that some people should feel the object of attacks on their religious beliefs in an unwarranted and offensive manner.” In particular, the Court noted the "provocative portrayal of God the Father, the Virgin Mary and Jesus Christ."[12]

However, CCHR-EXP experts note that "if at first the Court’s approach was to leave the States more chances to invoke [the "duties and responsibilities"] in justifying an interference with the freedom of expression, then the current jurisprudence of the Court leaves the States little discretion.”[13] In the same vein, Heiner Bielefeldt generally condemns criminal sanctions for blasphemous expressions which do not advocate for "violence or discrimination." These sanctions are deemed in principle "incompatible with the provisions of freedom of religion or belief and freedom of expression."[14] The State cannot sanction blasphemy as such, even when it shocks a large part of the population. The national margin of appreciation thus becomes limited to the evaluation of cases of expressions advocating for "violence or discrimination." The comparison between the decisions Otto-Preminger-Institut v. Austria of 1994 and Sekmadienis Ltd. v. Lithuania of 2018 demonstrates this evolution. Indeed, the ECHR seems today to neglect both the offense felt by believers and the fact that Catholics represent the main religion of the country. Furthermore, the Lithuanian advertisements are paradoxically more protected than the Austrian film, whereas they do not bring, contrary to the film, "merit as a work of art" or "contribution to public debate."

The reports of the CCDH - EXP and Heiner Bielefeldt also show an evolution in the way of assessing religious feelings of the population.

In the case-law of the European Court, "the emphasis has shifted from subjective feelings of followers of specific religious faith to a more “objective” evaluation of the public sentiments, and (...) the current approach favours an anti-conformist choice of individual persons."[15] Therefore, in the case Sekmadienis Ltd. v. Lithuania, the ECHR tends to dissociate the opinion of Catholic representatives from that, unknown, of the faithful who remained silent on this affair. This kind of dissociation certainly matches a social reality in some cases, but it should not be seen as the general case. Indeed, the Catholic Church is a structure based on obedience in the hierarchy and to which 77% of Lithuanians freely and knowingly declare to belong. The Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief also asks to pay special attention to “freedom of expression but also (...) freedom of religion or belief (...) of members of religious minorities, converts, critics, atheists, agnostics, internal dissidents and others”[16] By deliberately favoring "anti-conformist" religious choices, that is to say opposing institutional religions, the Council of Europe and the UN seem to judge the legitimacy of people's beliefs.

The judgment Sekmadienis Ltd. v. Lithuania shows this evolution. In Otto-Preminger-Institut v. Austria, the European Court "stated that it could not disregard the fact that the Roman Catholic religion was the religion of the overwhelming majority of Tyroleans."[17] While the Catholic faith is - as we have seen - shared by 77% of Lithuanians and the Christian faith by 83%, the Court does not draw the consequences of these sociological data in the case Sekmadienis Ltd. v. Lithuania. On the contrary, the ECHR refers several times to the "pluralistic" Lithuanian society (for example, § 81). The Strasbourg Court thus gives disproportionate significance to the 6.1% of Lithuanians who say they do not have a religion.[18] The morals and religion of the Lithuanians, which reveal a lack of pluralism and a national unity, do not even seem to be understood as sociological data that the Court must recognize. Whether pluralism is a social reality or not, it is in any case considered by the ECHR as an ideal that all countries should adopt. Society is not considered as it is, but as it should be according to a liberal and progressive ideology.

The duties and responsibilities constituting freedom of expression are neglected and "anti-conformist" religious choices are favored. Religious and moral relativism is therefore not an observed fact but a political and ideological choice imposed by the Council of Europe and the United Nations on reluctant peoples.

The need to protect the search for truth and the rational debate

The dissemination of gratuitously offensive images, useless for the debate and endangering morals can be legitimately restricted, especially if they are commercial advertisements. Furthermore, it is essential to make a distinction between the dissemination of such advertisements and the legitimate right to criticize religions. The ECHR noticed this difference but gives it no significance. Thus, “in the Court’s view, even though the advertisements had a commercial purpose and cannot be said to constitute “criticism” of religious ideas, the applicable principles are nonetheless similar” (§ 81). The European Court therefore gives a similar treatment to different situations, which is contrary to the principle of equality. Yet it is not the freedom to freely offend believers in order to sell clothes that should be protected, but the right to criticize religions and to debate religious subjects. Indeed, the protection of the feelings of religious people must not be absolute and the right to criticize religions is valuable and legitimate.

Although Christianity is the target of the Lithuanian advertisements, the broader context in which Muslim communities challenge freedom of expression makes it easier to understand the ECHR approach. It is in fact the fear of a censorship of freedom of expression by Islam that seems to lead the Court to disregard the offense felt by Lithuanian Christians and to identify permissive general principles. Indeed, the Strasbourg Court has to settle more and more disputes about freedom of expression on the Islamic religion and rightly wants to protect the ability to provoke in order to break idols and generate debate. This freedom must in fact be protected even when Muslim communities try to impose censorship by violence, including assassinations for instance on January 7th, 2015 at Charlie Hebdo's premises in Paris. The news related to Islam disturb the appreciation of the European Court and the disproportionate reactions of Muslim believers refusing any criticism of their religion incite judges to ignore in general the opinion of religious communities, even the most peaceful ones.

Nevertheless, it is difficult (if not impossible) to apply the same rules to religions that do not have the same relationship to rational debate and sincere search for truth. Indeed, while Christian communities sometimes complain about offenses aimed at hurting gratuitously and having therefore a negative impact on society as a whole and on morals, Muslim communities tend to react strongly and systematically in order to block debate, as shown by two pending cases at the ECHR. The ECLJ submitted written observations to the European Court in the case E.S. v. Austria (n° 38450/12) to explain that the statement in question referred to an established historical fact, that is, the marriage of Muhammad to a six-year-old girl (Aisha). The statement was therefore not intended to offend gratuitously, but to express a constructive criticism of Islam in order to contribute to a debate on religion and on the current practice of the marriage of pre-pubescent girls in some Muslim countries.[19] Similarly, in the case Smirnova v. Russia (n°50228/06), the applicant's reproduction of the Muhammad cartoons of the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten was a provocation aimed at highlighting the lack of freedom in Islam and the radical Islamic violence, which have been substantiated by facts since the beginnings of Islam and until today.

Trying to identify principles applicable to all religions is illusory and leads the ECHR to despise religion in general and its relationship with morals.

Despite the current context of the tumultuous development of Islam in Europe, it is essential to revive the centuries-old European tradition of disputation on religious subjects.

In a disputation, it is not the force or the interest that triumph, but the factual truth and the correctness of the arguments. Christianity developed thanks to disputations from the beginning, in particular the "sharp dispute and debate" about Jewish prescriptions, reported by the Acts of the Apostles (Acts 15). The context of the development of universities at the end of the Middle Ages led to many disputations on theological topics.[20] It was also during a disputation in Valladolid in the 16th century that the Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas was able to demonstrate that the Amerindians had a soul. Religious debates based on reason and mutual respect also took place between Christians and Muslims, for example when Saint Francis of Assisi and the Sultan of Egypt Malik al-Kamil met in 1219, despite the context of the Crusades.[21] In his lecture of September 12th, 2006 in Regensburg on the relationship between reason and faith, Pope Benedict XVI tried to initiate a disputation about religion, which was unfortunately refused by a large part of Muslim religious leaders.

For the sake of peace, the various institutions and courts must promote the rights and freedoms encouraging the sincere search for truth, including religious truth, and open debates based on reason and combining firmness and courtesy.

[1] Statistics from the 2011 census: https://osp.stat.gov.lt/documents/10180/217110/Gyv_kalba_tikyba.pdf.

[2] Steering Committee for Human Rights, « Analysis of the relevant jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights and other Council of Europe instruments to provide additional guidance on how to reconcile freedom of expression with other rights and freedoms, in particular in culturally diverse societies », July 13th, 2017 : https://rm.coe.int/analysis-of-the-relevant-jurisprudence-of-the-european-court-of-human-/1680762b00, § 68.

[3] CDDH report, supra, § 68.

[4] Statistics from the 2011 census.

[5] Statistics from the 2011 census.

[6] Steering Committee for Human Rights of the Council of Europe, “Extract of the terms of reference given by the Committee of Ministers to the CDDH regarding the work of the CDDH-EXP during the 2018-2019 biennium,” January 8th, 2018: https://rm.coe.int/extract-of-the-terms-of-reference-given-by-the-committee-of-ministers-/168077b6f6.

[7] CDDH report, supra.

[8] Human Rights Council, Document A/HRC/31/18, December 23rd, 2015.

[9] CDDH report, supra, § 90.

[10] Ibid., § 31.

[11] Ibid., § 32.

[12] Ibid., § 90.

[13] Ibid., § 44.

[14] Special Rapporteur report, supra, § 61.

[15] CDDH report, supra, § 95.

[16] Special Rapporteur report, supra, § 60.

[17] CDDH report, supra, § 90.

[18] Statistics from the 2011 census.

[19]ECLJ, Written observations submitted to the ECHR in the case E.S. v. Austria (application n°38450/12), May 25th, 2016 : http://9afb0ee4c2ca3737b892-e804076442d956681ee1e5a58d07b27b.r59.cf2.rackcdn.com/ECLJ%20Docs/Obs.%20Aff.%20ES%20c.%20Autriche_001.pdf.

[20]On this subject, see : Jacques Le Goff, Intellectuals in the Middle Ages, translated by Teresa Lavender Fagan, Oxford: Blackwell, 1993.

[21]On this subject, see : Albert Jacquard, Le Souci des pauvres : l'héritage de François d'Assise, Calmann-Lévy, 1996.