The ECHR is looking into the abuses of euthanasia in Belgium

ECHR: abuses of euthanasia in Belgium

The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) has agreed to consider the application introduced by a man whose mother was euthanized without him or his sister being informed. Priscille Kulczyk a Research Fellow for the European Center for Law and Justice (ECLJ), worries about the abuses of this practice in Belgium.

The ECLJ was authorized to submit Written Observations in the case (available here).

Opinion published in FigaroVox on 23 July 2019.

Victim of what is no less than a euthanasia by deprivation of water and food because of his heavy handicap, Vincent Lambert had not yet closed his eyes that the supporters of euthanasia were already dreaming of a legalization of this practice in France, while praising the merits of the Belgian laws relating to the end of life. Yet these, and particularly the law on euthanasia, leave the door wide open to serious abuses. It is precisely on such drifts that the ECHR is looking for the first time with a case Mortier v. Belgium.

The Court has ruled several times concerning people demanding a “right to assisted suicide” (Pretty v. The United Kingdom in 2002, Haas v. Switzerland in 2011, Koch v. Germany in 2012, Gross v. Switzerland in 2014). It also validated “disguised euthanasia” by end of care of disabled patients such as Charlie Gard and Vincent Lambert (Lambert and Others v. France in 2015, Gard and Others v. The United Kingdom in 2017). With the Mortier application, it is therefore also the first time that the Court must decide on such a procedure when the person concerned has already been euthanized.

It is worth remembering the facts. Ms. Godelieve De Troyer, suffering from chronic depression for more than 20 years, was euthanized in 2012 without her children being informed. Indeed they were informed on the day after her death. Her son, Tom Mortier, complained before the Court of the failure of the Belgian State to protect his mother’s life, stating that the legislation on euthanasia had not been respected and there had been no effective investigation of these facts which he had however reported to the Courts. In particular, he denounced the lack of independence of the Federal Commission for the Control and Evaluation of Euthanasia (CFCEE) responsible, a posteriori, of controlling the legality of the euthanasia. In particular, he reproached the fact that the doctor who euthanized his mother is himself the president of this Commission but also of the association LevensEinde InformatieForum (LEIF) which militates in favour of euthanasia. Yet his mother gave €2,500 to said association shortly before her euthanasia.

A law on euthanasia ill adapted to mental suffering

This application perfectly illustrates the systemic flaws in the Belgian regulation of the practice of euthanasia and the serious abuses and excesses resulting from it. The current application is unfortunately not a textbook case, for the media regularly talk about controversial euthanasia in Belgium. And many denounce the laxity with which the Law of 28 May 2002 on euthanasia was implemented.

According to the conditions initially provided in this Law, euthanasia must be the object of a “voluntary, well-considered and repeated” request, from a “legally competent and conscious” patient, who suffers from a “condition of constant and unbearable physical or mental suffering that cannot be alleviated, resulting from a serious and incurable disorder caused by illness or accident”. Yet the wording is unclear and subjective: suffering itself is a subjective notion, just like its being unbearable, as attested by the CFCEE. In case of mental suffering, its not being relievable is also almost impossible to determine, as shown by the publicized case of Laura-Emily, 24 years-old, who was suffering from depression and, having asked to be euthanized, changed her mind on the D-day, explaining that she had better supported the previous weeks of her life. Thus, the possibility of euthanasia because of mental suffering is highly problematic. Besides, in 2002, the Public Health Committee of the Chamber unanimously opposed to include it in the law, rightly considering that such suffering is too subjective and its weight almost impossible to evaluate. It also emphasized the ambivalence of the will of psychic patients. Thus, in case of depression, the affection suffered by Mrs. De Troyer, the demand for euthanasia is more a symptom of pathology than a free and thoughtful demonstration of will.

Moreover, there is a paradox in claiming to offer a right to assisted suicide or euthanasia - in the name of respect for individual autonomy - to people who precisely do not have a mental balance. Respect for autonomy should, on the contrary, lead to the prohibition of euthanasia for people with depression or mental illness. These people, who are “disabled” within the meaning of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, should be protected and not exposed to suicide. But protection is unfortunately impossible in practice since the Belgian law does not prohibit the “medical shopping” which consists, for a patient facing the refusal of the doctor who usually follows him, to reiterate his request for euthanasia with other doctors until to find the one who is favorable, that is, the most lax or militant. Ms. De Troyer has also used this practice.

CFCEE, an instance favouring abuses?

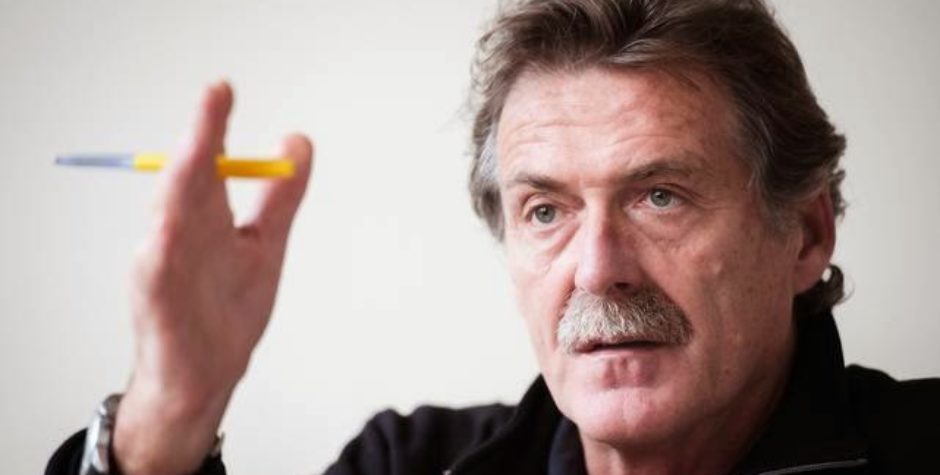

One would think that the Federal Commission for the Control and Evaluation of Euthanasia, the body responsible for verifying that euthanasia was practiced in compliance with the legal conditions and procedures established by the law of May 28, 2002, would compensate for the flaws of the latter. This is not the case, as the Mortier request once again shows. The CFCEE is cruelly lacking impartiality, since out of the 16 permanent members, at least 8 (and at least 6 of the 16 alternates) belong to associations that advocate euthanasia (for example, the presidents of LEIF and of ADMD) and / or are doctors practicing euthanasia themselves. This is the case of its Dutch-speaking president, Dr. Wim Distelmans (picture), who is none other than the doctor who euthanized Mrs. De Troyer! On several occasions, the CFCEE has also confessed its inability to carry properly out its mission because it is based on a declarative system and therefore dependent on the professional conscience of doctors. And Dr. Distelmans added: “suspect cases, of course, doctors won’t declare them, so we do not control them” (Complément d’enquête : « Santé, GPA, vieillesse : quand l’homme défie la nature », France 2, 2014). Yet studies show that, for example, about half of the euthanasia in Belgium had not been declared in 2007. Moreover, if the terms of the law on euthanasia are indeed vague and subjective, the Commission steps into the breach by interpreting them in an excessively extensive and liberal sense. For example, here is a selection of its decisions: according to her, the coexistence of several non-serious and non-incurable pathologies fulfils the requirement of a serious and incurable condition; it has also approved cases which sounded like physician-assisted suicide when it does not fall within the scope of the law; it seems that it validated an “in-duet” euthanasia obtained by a couple, with one of its members not terminally ill.

Finally, one can question the utility of an a posteriori control, that is to say once the euthanasia has taken place, which obviously does not aim to protect the life of people and is particularly unsuitable in case of euthanasia because of mental suffering. Is it thus surprising that between 2002 and 2016, the CFCEE only transmitted to the public prosecutor a single file out of 14573 euthanasia? Members both judges and judged, conflicts of interest, bias, a posteriori control and declarative system, broad interpretation of the terms of the law: the CFCEE proves ineffective to prevent abuses, quite the opposite. Thus one of its members, a doctor, recently resigned, accusing it of not having brought to justice a doctor who had euthanized a patient at the request of his family.

A case questioning the entire system regulating euthanasia in Belgium

The Belgian State is therefore clearly failing to meet its obligations under the Convention whereas the ECHR held that “Article 2 (…) creates for the authorities a duty to protect vulnerable persons, even against actions by which they endanger their own lives” (Haas v. Switzerland, §54). What the Court will decide in this case will inevitably have heavy consequences because the scope of the Mortier application goes far beyond its own scope: it puts into question the entire system regulating euthanasia in Belgium by showing how much it proves defective and its safeguards illusory. While the Court stated that “the risks of abuse inherent in a system that facilitates access to assisted suicide should not be underestimated.” (Haas v. Switzerland, §58), this case confirms that this risk is real, gives a concrete insight into such abuses and lets us catch a glimpse of the consequences on a large scale.

Indeed, far from concerning only the person who asks for it, euthanasia and its modalities have profound and fatal social consequences: first of all, psychological consequences on the family members of the deceased, but also loss of confidence in the family in general and mistrust towards caregivers; weakening of vulnerable people, some of whom are incited to commit suicide. It would be abusive and dangerous to make the autonomy of a patient prevail as a supreme ethical value to justify a practice prejudicial to the whole society and thus questioning the common good.

It would therefore be practicing an ostrich-like approach towards the excesses of euthanasia to not condemn the State in this case, while the trivialization of the euthanasia mentality in Belgium is real and wreaks havoc. For example, the cases of euthanasia without obtaining the consent of the person, the opening of euthanasia to minors “endowed with faculties of judgment” without age limit in 2014, as well as the official figures: from 235 euthanasia in 2003, their numbers grew rapidly each year to 2537 in 2018, which represents 2% of the total annual deaths. In this context, one should also note that three studies have recently revealed that “40% of Belgians are for the end of care for people over-85” (Le Soir.be, 19.03.2019). If the Court does nothing, it will complete the anticipatory novel published in 1907, Lord of the World where the author, Robert-Hugh Benson imagines houses of euthanasia, where “by unanimous consent, the useless, the dying were delivered from the anguish of living; houses specially reserved for euthanasia [proved] how much such emancipation was legitimate.”